By: Keith McCambridge and Michelle Daisley

This article originally appeared on the NACD blog, BoardTalk on October 7, 2020.

Demands on directors have increased dramatically in recent years, and boards have struggled to stay on top of the challenges presented by an increasingly dynamic, volatile, and ambiguous world. Climate change has multiplied the challenges facing directors by significantly complicating risk oversight. Of course, providing risk oversight and protecting the interests of shareholders is just one aspect of the board’s role. High-performance boards act as enablers of competitive and organizational advantage, using their collective capabilities to create value, rather than acting as mere defenders and protectors of the organization’s current market position. Beyond just understanding and managing climate-related risk, the board must encourage management to look at the other side of the proverbial coin — climate-related opportunities. This is no small ask, and the degree of adjustment and change required of the board to recognize these opportunities and encourage management to pursue them should not be underestimated.

The effective functioning of a board can be viewed through two dimensions:

- Board Composition and Dynamics: The profiles, experiences, expertise, and capabilities of board members, both individually and collectively, and how they behave as a group to perform the board’s duties

- Organization and Operation: The setup and operations of the board and its committees, how agendas are set, what information the board receives, and how and when it is involved in key decisions and processes

Both dimensions must be considered before the board’s ability to respond to the challenges posed by climate risks can be enhanced.

Composition and dynamics

Professor Herminia Ibarra at the London Business School talks of the need for leaders and organizations to stop being “know-it-alls” in favor of becoming “learn-it-alls,” arguing that the speed of change that organizations currently face requires continuous learning and connection to the ecosystem in which they operate.

Without this, it is too easy for an enterprise to suddenly lose its relevance and, equally, for boards to lose their competency to protect shareholder interests and provide effective oversight of risks. Boards need to be open learning systems, not closed entities relying on their eminence and their historical experience of markets that have changed so much from how they functioned before that they are now unrecognizable.

The first step for any board to take is to accept its knowledge deficit and commit to continuous learning and exploration.

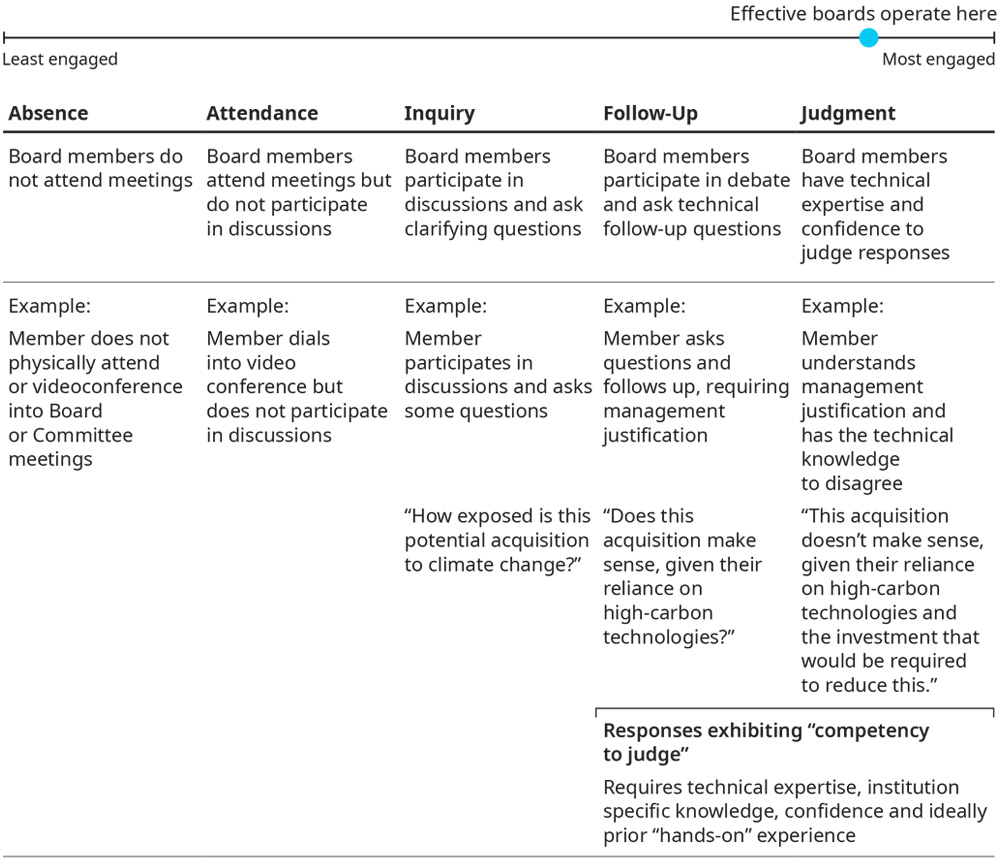

Climate change is new, unfamiliar, and was not part of the job description when many nonexecutive directors (NEDs) were executives themselves. This means that boards may lack the “competency to judge”. Exhibit 1 below shows a spectrum of engagement and challenge for board members: “What good looks like.”

TCFD climate-related disclosures and their relevance to the board and its committees

Source: Marsh & McLennan

So, how can directors build their “competency to judge”? In order to gain expertise in new areas, many boards have first looked at their own composition. Demand for NEDs with experience in digital transformation, climate change, sustainability, and regulatory issues has soared, yet this can create new problems. Boards only have authority as a collective — no one individual within a board has authority to act alone, and it is only this cabinet authority that gives a board its mandate. Boards can fall into a trap of appointing one NED who has experience with climate risk, which often leads to that NED being viewed as the “board expert” on climate risk — debate, discussion, and competent disagreement on this issue among the full board is forgotten.

This creates a single point of failure as no one feels able or equipped to challenge the views espoused by that expert. A single appointment of a director with specific expertise or experience is insufficient to equip the board with the collective competency to judge. The key to gaining the competency to judge lies in augmenting this expert view with additional strategies. Dedicating time to learning as a board is vital to the board’s development as an entity. This learning can be guided by the subject-matter expert but should also include input from management to ensure organizational relevance.

Increasingly, boards are experimenting with expert panels. Here, the board engages external and impartial individuals to augment their judgment. Expert panelists are not board members, nor do they carry any decision-making authority; their role is to bolster the board’s competency to judge. On occasion, these external individuals can attend board discussions to ensure that the right questions are being asked and that the responses are understood. This approach has been widely used in the area of digital transformation, where the technology and risks associated with migration or real-time replatforming are considerable. It goes without saying that these strategies to equip the board with the competency to judge are not fail-safe, but they do significantly increase the chances of informed oversight.

Board chairs need to create the right environment for board members to be pupils — not teachers. They need to develop a board environment that is conducive to the psychological safety required for constructive conflict among board members. Board members need to find the courage to reveal their lack of understanding, ask questions that encourage learning, and recognize their inadequacies. Increasing board diversity and introducing directors with more varied experience and unusual backgrounds (not necessarily climate expertise) can help to foster a culture of courage and challenge.

Organization and operation

One approach to building a climate-competent board is to establish a board sustainability committee. A dedicated committee, with the right mandate and members, can provide more focused attention on climate-related topics. However, with this approach there remains a risk of pigeonholing the issue away from full-board decision making, when climate change is in fact a whole-enterprise issue that touches upon many different board responsibilities.

A more holistic approach involves embedding relevant aspects of climate change into all key board decisions and processes. For example, climate-risk considerations should be part and parcel of all board discussions about strategy, risk, M&A, and innovation, as opposed to being a separate agenda item.

Directors should be satisfied that executives are actively considering climate implications and regularly providing information to the board. Directors should challenge executives if this does not happen. To enable this, the board needs to set clear expectations for management reporting and accountability.

The board is being transformed by the very environment in which it now operates. Today’s first-class directors possess qualities that are different from those of board members in the past. Knowledge is becoming less valuable than the capacity to learn. The formality and eminence of boards are being replaced by humility, exploration, external connections, and the need for a boardroom climate of psychological safety that encourages constructive conflict.