Editor’s Note: The following article is part of an ongoing series offering our strategic advice and expertise on what healthcare industry stakeholders should do immediately in response to the rapidly evolving novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The United States now has more COVID-19 cases (over 82,000 confirmed cases across all 50 states) than China and Italy do. Hospitals nationwide could be stretched beyond their current capacity in serving COVID-19 patients should more dire pandemic projections come to pass. Intensive care units (ICUs) and equipment shortages including devices like respirators will be the hardest hit in a rapid patient surge.

But routine beds are also at risk of being overrun. In some states like New York, we’re already in the midst of a surge. In other places, a surge may be weeks out. No matter the case, every system should plan what they’ll do when their own system is at capacity.

Even under the best of circumstances, the system operates at or near capacity. Should that happen, both COVID-19 and other patients will be at serious risk, as being without a bed means being without a place to go.

Four Tactics for Managing Patient Flow and Length of Stay

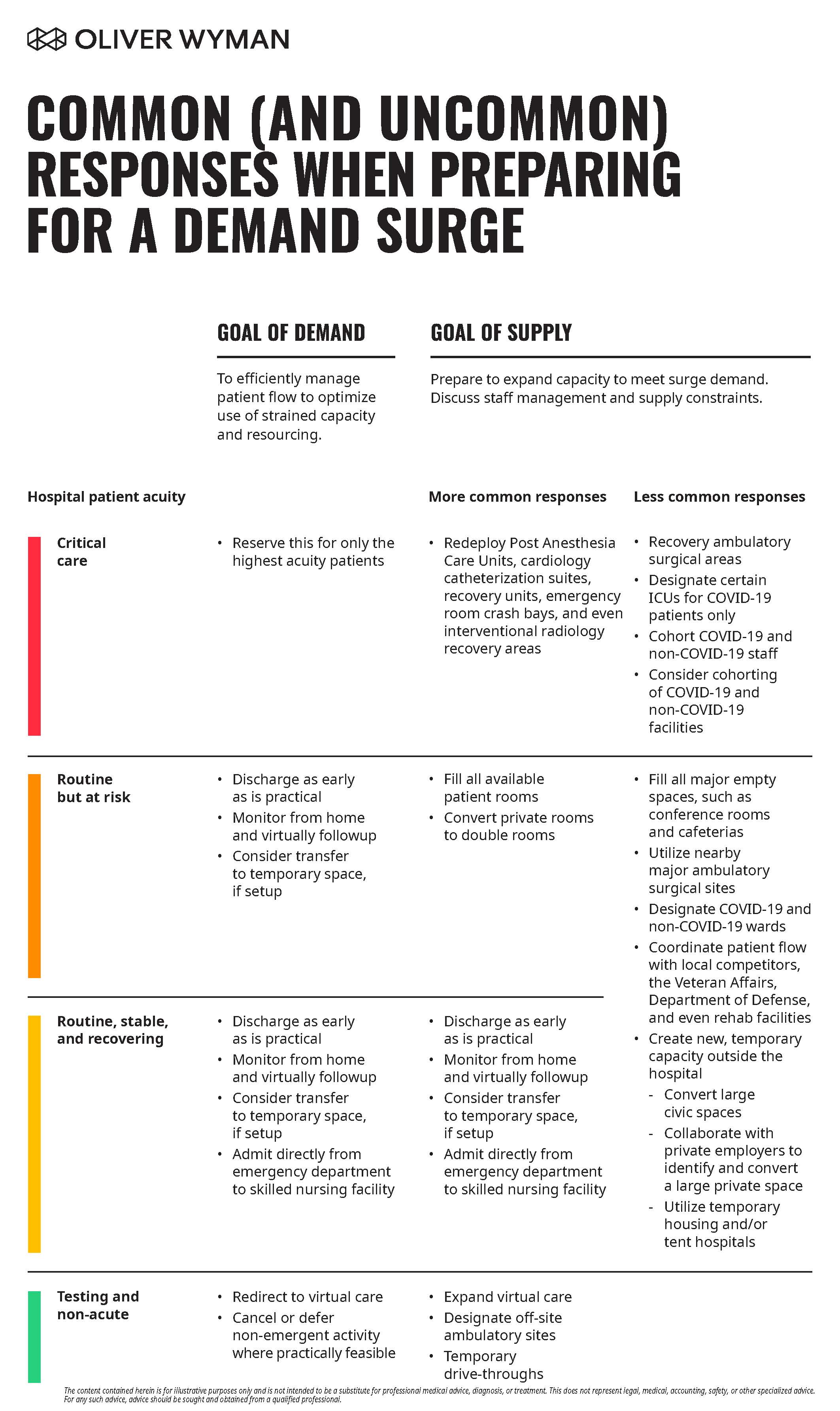

To optimize available capacity and expand routine bed capacity within your existing campus, here are some ways to convert ICU capacity and leverage off-campus capacity.

1. Manage both patient flow and length of stay to optimize capacity.

Matching limited critical care space and resources with patients who need them most will be paramount in minimizing mortality and maximizing hospital effectiveness. To optimize current capacity to contend with a surge in demand, consider:

Actively navigating patients to a minimally appropriate care level: Critical care beds and resources for managing the highest acuity patients will be the first to get tapped out. Only the highest-need patients should be admitted to critical care. And they must be navigated down through the acuity pyramid as early as it is clinically feasible to make room for incoming patients in higher need.

Proactively discussing clinical risk tolerance and clarifying protocols: Clinicians and administrators strive to ensure high-quality patient care. As a result, hesitations to limit care for elective procedures have become very real. However, when demand approaches or exceeds supply, uncertainty may hamper throughput and limit essential care for those patients with heightened needs. In anticipation of a surge, leaders should establish protocols and capacity management policies designed to minimize risk and maximize outcomes for the greater patient population being served. This is best done through clarification of clinical protocols and triaging for peak surge scenarios.

Ensuring rapid COVID-19 test results: Rapid turnaround is essential for proper placement of patients, yet this remains a challenge. Ongoing urgent focus is critical as new tests are developed, approved, and rolled out. Have processes in place to administer and process tests and manage information flows to providers and patients.

Transitioning discharge-eligible patients: As patients’ conditions improve, discharge them as soon as they can safely be managed at home. Providers must align on how to best manage this process, as well as the patient mandated tools and guidance following their hospital stay. There may be value in preparing to arm discharged patients with many of the same tools used to sustain low acuity COVID-19 patients in their homes. (For more on maintaining care in the home, read When Patients Need COVID-19 Home Care.)

2. Expand routine bed capacity within the current campus.

To gain economies of scale (particularly with labor shortages), an immediate solution is to expand medical bed capacity inside core inpatient facilities. That means deploying all spare beds to fill all available patient rooms. And, converting private rooms to double rooms. If pushed to the full extent, this would expand capacity beyond licensed bed counts, which will require the State Department of Health’s approval. Staffing and respirators will be a key constraint here.

Consider the following strategies:

Designating entire wards (or even floors) for COVID-19 versus non-COVID-19 patients. This will potentially improve things staff control, material and patient flow, and communications during a surge period. This will require all patient wards to handle a broader clinical spectrum of acute needs, which makes earlier preparation and rapid (re)training essential. Simple facility isolation techniques can be quickly implemented, like adding physical barriers and doors between units, along with appropriate signage, or limiting badge access to certain floors or doors.

Additional steps to consider inside the facility include:

Using all major empty spaces: Any large, open space such as conference rooms and cafeterias may be filled with beds or even cots for lower-level acuity care and observation.

Nearby major ambulatory surgical sites: Consider utilizing nearby multispecialty centers and surgical centers for care of lowest acuity, non-COVID-19 patients requiring extended observation, and more routine, emergent care.

3. Develop plans to convert spaces into ICUs.

It may be necessary to expand ICU capacity if COVID-19 spread continues. Redeploy post-anesthesia care units (PACUs), cardiology catheterization suites and recovery units, crash bays in the emergency department (ED), and even interventional radiology recovery areas. These are natural opportunities to extend ICU capacity, especially given that elective and non-emergent volumes through these units may be deferred while the hospital contends with the pandemic.

Other steps for increasing ICU capacity include:

Designating certain ICUs for COVID-19 patients only: Separating COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 spaces will alleviate issues in personal protective equipment (PPE) utilization and allow more efficient use of space. This way COVID-19 patients are less likely to infect one another. This likely requires flexing the scope of patients that non-COVID critical care areas serve.

Separate COVID-19 and non-COVID staff: Separation of clinical and non-clinical staff serving COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients will reduce testing requirements and allow for a freer flow of each cohort serving their respective area. Housekeeping and dietary staff, for instance, should be assigned only to one area or another and grouped with patients and the nurses. Physicians should also be split up if numbers permit.

Splitting COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 facilities: Systems with multiple facilities in closer proximity can consider designating entire sites as COVID-19 versus non-COVID-19, as in past outbreaks. Similar coordination for separating facilities may also be feasible across multiple, different hospital systems if the hospital and local government leaders find it practicable.

Recovery areas in ambulatory surgical units: This may require waivers from the state department of health, and potentially from federal requirements (which appear to be in flight).

4. Make plans for tapping temporary off-campus capacity.

If the need for inpatient care continues to escalate, hospitals and health systems may have to draw on temporary, offsite capacity. While this option is subject to constraints around equipment, supplies, and clinicians, providers in capacity-constrained communities must develop contingency plans. Here are some options to consider:

Admit directly from the ED to a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF): Non-COVID-19 patients, such as those with bacterial pneumonia, may be admitted straight to an SNF, presuming waivers can be secured from payers and payer utilization management protocols can be paused.

Coordinate with local competitors, Department of Defense facilities, Veterans Administration sites, and even rehabilitation facilities: Although these facilities will face their own pressures, all available beds in the market should be utilized.

- Convert large civic spaces: Local school gyms, event halls, and even larger indoor tennis courts may be set up to house COVID-19 patients with mild to moderate symptoms for observation and lower acuity care.

- Collaborate with private employers: Various private spaces may be utilized, such as hotels, motels, and indoor sports facilities. Even airplane hangars could be converted temporarily.

- Contact FEMA to identify temporary housing units: Mild-to-moderately ill COVID-19 patients and potentially infected, asymptomatic individuals may be housed in THUs while awaiting test results.

- Tent hospitals: Larger open areas may be used to set up field hospitals. In a state of emergency, military and government support may be mobilized to accomplish construction and manage operations.

It’s impossible to know how long such setups will be needed (if at all). So, here are two additional considerations in preparing for the unknown:

- Enlist outside parties to assist in preparation: Recruiting additional support through local civic administrations, large employers, and community organizations for planning and execution may add bandwidth and expediency in identifying and evaluating space and logistics options (though it will add complexity when done in coordination).

- Consider trade-offs for extended use: If local COVID-19 containment efforts prove insufficient, there is a (smaller) chance hospitals will be overburdened for many weeks. Consider that temporary capacity may be more durable if they are larger, weather-resistant, have more space for worker movement, sanitation infrastructure (toilets and washrooms), and larger supplies space.

Some of these actions can be deployed much more quickly than others, but none are easily deployed once a surge takes place. Hopefully, containment will be effective and more drastic measures will prove unnecessary. It’s these steps that may save lives in a time when so much is unpredicted and unknown.

The content contained herein is for illustrative purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This does not represent legal, medical, accounting, safety, or other specialized advice. For any such advice, advice should be sought and obtained from a qualified professional.