You can download the full Global Fleet and MRO Market Forecast 2023-2033 here.

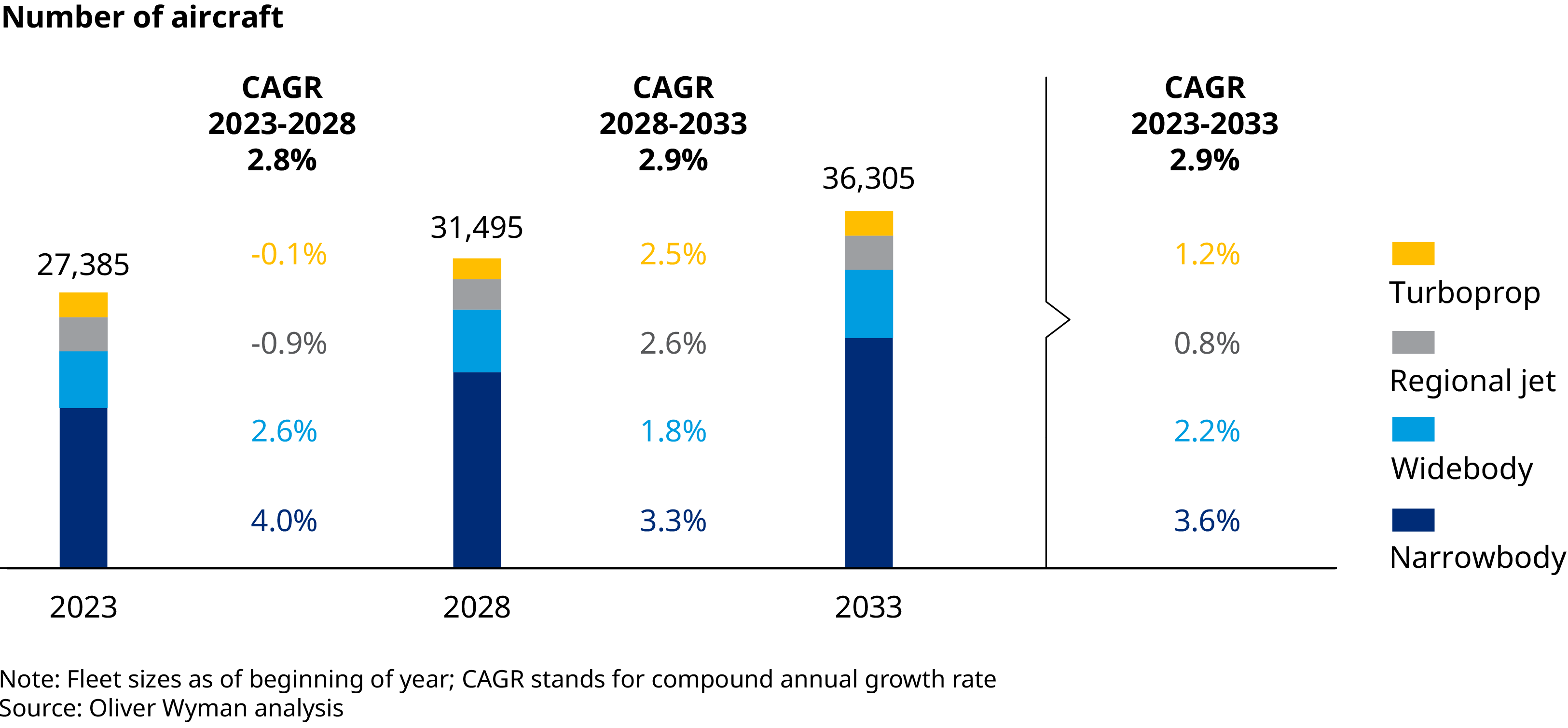

The worldwide commercial aviation fleet will expand 33% to over 36,000 aircraft by 2033 — a compound annual growth rate of 2.9% — according to Oliver Wyman’s Global Fleet and MRO Market Forecast 2023-2033. Today the fleet numbers almost 27,400, just short of its size in January 2020 — the last month before COVID-19 changed the economy and everyday lives around the globe.

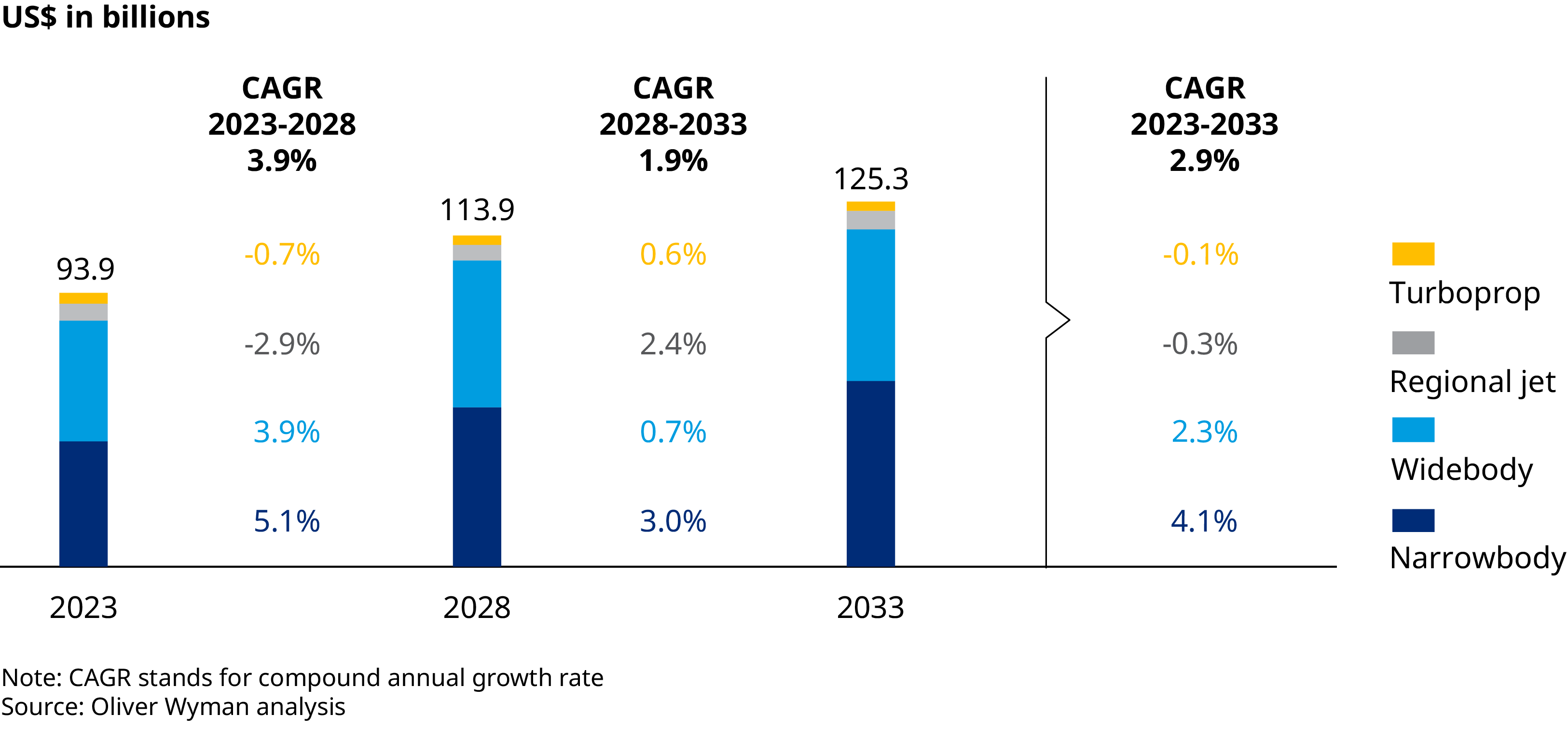

Aviation’s global aftermarket, which provides the maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) services to keep the fleet flying, is also expected to grow another 22% this year, topping $94 billion — a mere 2% below its 2019 peak. By 2033, it will reach $125 billion — a compound annual growth rate of 2.9%. In 2022, MRO demand expanded 18%.

Meanwhile, we anticipate a record number of aircraft deliveries over the next 10 years, despite current supply chain constraints that may make it hard to meet this year’s targets. And despite rising air fares and a year of delays and cancellations in many of the world’s biggest markets, travelers seem undeterred. By December, global passenger traffic — domestic and international combined — reached 82% of the 2019 total. That’s the highest level since the pandemic.

A tough year in aviation

It’s not like the rebound year 2022 was easy either. While vaccines and treatments stemmed COVID in North America and Western Europe, China suffered outbreaks that triggered its zero-COVID policy, leading to the lockdowns of Shanghai and other large cities and closure of some MRO facilities and aerospace parts production.

Global supply chains had already been disrupted since 2020 by the coronavirus. On Feb. 24, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin attacked Ukraine, killing thousands and throwing trade and commodity markets into disarray over potential shortages of Russia’s titanium, nickel, aluminum, and oil and gas and Ukraine’s grain production.

That said, the most vexing challenges for aviation were widespread labor shortages across every sector of aviation and in most regions. In North America, the industry is facing two potentially severe shortfalls in the ranks of commercial airline pilots and aircraft mechanics. By our analysis, the supply gaps already amount to 18% of the total pilot workforce in 2023 and 14% of aviation mechanics. The outlook is for those deficits to grow or at least linger through 2033. The gap in the number of pilots needed and those available has already led to reductions in service to less popular and more rural destinations and has hit regional airlines hardest.

But the shortfall of aviation workers is a global problem. European ground crew shortages were so ubiquitous and severe in 2022 they led to the imposition of capacity limits at some European airports, including London’s Heathrow and Amsterdam’s Schiphol. In India — the fastest growing aviation market according to our latest Fleet and MRO Forecast — the desperate need is for more air traffic controllers. But in aviation so many jobs are critical to operations that any ongoing shortage can eventually result in the industry’s growth being limited not by a lack of demand but by supply constraints.

Aircraft demand

The labor shortages contribute to supply chain snarls that have already led to longer lead times on parts — sometimes of more than a year. And the stress on supplier capacity is only likely to multiply once Airbus and Boeing, the globe’s largest aircraft manufacturers, begin to implement planned higher production goals, which would be difficult to meet even if supply chains were functioning well. Some of their biggest suppliers have publicly suggested the elevated production may be beyond what they and the rest of the supply chain can handle.

But the higher production is only a reflection of the growing demand for aircraft. In February, Air India placed the largest aircraft order in history — 470 aircraft, valued at somewhere around $85 billion. Airbus will supply 250 aircraft, and Boeing 220. The order is primarily for narrowbody aircraft, but it also included 787 Dreamliners from Boeing and A350s from Airbus, both widebodies. The carrier has an option to buy an additional 370 aircraft.

Overall, Oliver Wyman forecasts 20,600 new production aircraft to be delivered over the next 10 years. Most will be narrowbodies where the demand is the strongest. We forecast narrowbody production to reach 1,550 by 2026.

The increase in the size of the fleet is fueling demand for MRO as well. Engine MRO has historically represented the biggest piece of the MRO market and remains so today. In 2023, engine MRO is expected to exceed 2019 levels, helping the overall MRO market to rebound. This recovery comes a year earlier than previously forecast because of the rapid return of air travel demand and utilization. Over the forecast period, engine MRO is expected to hit $63 billion by 2033, representing compound annual growth of 4%.

The future of aviation

Over the next decade, aviation’s drive to expand is likely to bump up against various limitations from an overwhelmed supply chain, labor shortages, and new rules on emission reduction. That will push the industry to either develop innovative solutions or scale back.

One area that will test aviation is climate change and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. While it has been overshadowed by more immediate pressures like COVID-19, labor shortages, and the supply chain, it will likely become a more important issue with which aviation will have to contend as the decade progresses. Just recently, France enacted legislation that would prohibit air flights between distances which are served by a train ride of 2.5 hours or less. Several other European countries are working on similar rules. While not onerous, the new prohibition may be a sign of more restrictions to come, particularly in Western Europe.

The other challenge is the insufficient production capacity for sustainable aviation fuel, the most immediate tool to cut emissions. SAF, which emits 50% to 80% fewer emissions than conventional jet fuel, is currently a pricey substitute. Based on our calculations, the best-case scenario for a 2030 supply is 5.4 billion gallons when the industry would require 16 billion just to keep airline emissions at 2019 levels.

While the demand for air travel will be there, the capacity to meet it may not always be — a challenge the industry can’t afford to ignore. But for now, aviation is on a growth trajectory.