The latest merger announcements such as Aetna-CVS, Humana-Kindred, and others raise immediate concerns of how to maintain stability and financial security. It is unknown if mergers such as these will bring quality, affordability, and accessibility to healthcare consumers.

Consider CVS-Aetna, which promises to provide high touch patient care, access to convenient, high quality, low cost healthcare at your nearest drug store, and an alternative solution for absorbing emergency department patients over flow. CVS-Aetna’s goal is to keep more patients out of the hospital, all while transforming payments to value-based versus fee-based care. Their ultimate vision is to deliver consumer-centric care in an affordable care setting, starting with the patient’s home.

CVS and Aetna will potentially provide unmatched access for consumers. For starters, there are 22 million Aetna members. And CVS has 1,100 minute clinics nationwide, with potential to expand to as many as 9,600 pharmacies – including those pharmacies recently acquired by Target.

But This is Perhaps Just the Beginning for Healthcare

A combined CVS-Aetna will create the third largest commercial health insurance in the nation – just like that of its biggest competitor (and the nation’s largest health insurance company), UnitedHealth Group. Nonetheless, those health systems fearing competition from the latest CVS-Aetna announcement are perhaps also feeling pressure from UnitedHealth Group, which has been buying up physician practices, urgent care facilities, and surgery centers through the OptumCare unit of Optum subsidiary.

Optum, with over 200 MedExpress urgent care and walk-in centers and about 30,000 clinicians, now plans to buy even more medical care providers nationwide. And Optum’s latest $4.9 billion cash purchase of Davita’s Medical group, with over 1.7 million patients, will improve healthcare access across an additional 300 medical clinics.

Mergers May Change Concepts of Cost in Healthcare

Mergers, whether horizontal or vertical, are exceedingly difficult to integrate, culturally and operationally, and mostly create more complexity; vertical mergers have additional complexity in that they may signal different corporate objectives and create confusion at the enterprise level regarding the identity of the new organization.

With all of this merger activity underway, the healthcare market is nonetheless now realizing traditional health systems may not necessarily promote greater affordability, accessibility, and patient convenience. Although the role of traditional health systems will still be critical when it comes to highly acute cases, acute facilities and hospitals may become a cost center versus a profit center. Skeptics think we have yet to see vertical or horizontal mergers and acquisitions deliver significant values, and the jury is out on the recent ones.

The central question for health systems is: Do they consider recent merger activities a threat? Or, should they just keep their heads down and believe health systems will always remain the focal point, no matter what actions the traditional stakeholders and new entrants to the health market take?

Take Action to Keep From Falling Behind the Competition

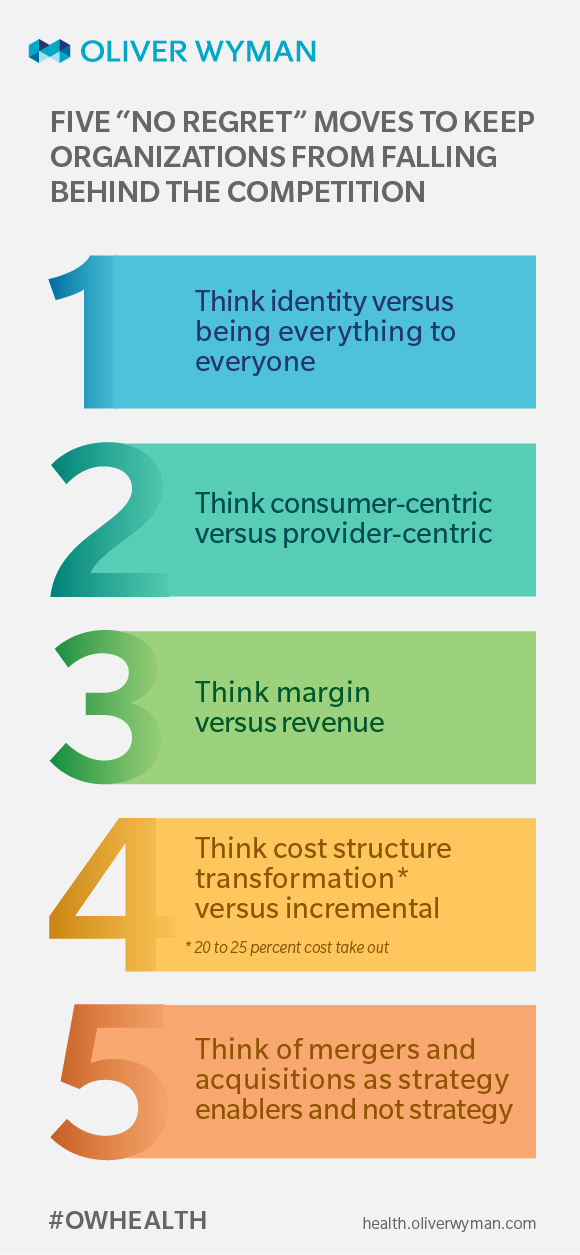

Regardless of whether or not you feel threatened by CVS-Aetna, UnitedHealthcare, Optum, and others, here are a number of actions health system can take that are “no-regret” moves to help maintain organizational stability and financial sustainability:

- Think identity versus being everything to everyone: Market trends of shifting to pay-for-performance, shifting from wholesale to retail, regulatory shifts, and new competitors in the market have created margin pressure and identity crises for health systems. As a result, they need to define their strategy and be deliberate about their choices and trade-offs based on their strategy.

- Think consumer-centric versus provider-centric: The majority of health systems have designed care delivery around clinicians versus consumers. Although state consumer-centricity is important, the basics for consumer centricity have been slow to put in place. Among them: access, where to “enter” the health system, how to navigate (many hand-offs with unclear logic), transactional versus personalized care, lack of transparency on cost at the point of service, and putting provider satisfaction above consumer satisfaction.

- Think margin versus revenue: The majority of health systems are designed and focused on revenue maximization versus maintaining margin. This operating model has resulted in complicating care delivery and generating waste and care delivery fragmentation. To put it into perspective, 4 to 5 percent loss of revenue will result in going from profit to loss for many health systems, as most of the not-for-profit health system margins are below 5 percent.

- Think cost structure transformation (20 to 25 percent cost take out) versus incremental: Cost is best treated as an investment versus expense. Every institution should ask the questions: What, where, and how well? What do we do? Where is it done? And how well is it done? Not surprisingly due to focus on revenue generation on a fee-for-service model, the cost question has not gotten the attention it deserves. Over the past five years, many health systems have put cost on their radar screen. However, the reduction has been incremental and most of the time unsustainable. Why? Because they have mostly relied on benchmarks to size the magnitude of the opportunity; and then incremental cost take outs have been implemented without business process redesign. So, cost was reduced without reducing the workload or answering the what, where and how questions. Benchmarking against systems that are inherently inefficient will only make you perform as well as your competition, if you consider your competition to be a health system. We now know that competition base is changing performance indicators with affordability as the central question.

- Think of mergers and acquisitions as strategy enablers and not strategy: In the past several years there has been significant uptick in M&A and partnerships. And in some reports, the number of deals between 2011 and 2016 increased by over 50 percent. The early driver was gaining scale and getting negotiation power against payers. Many M&As have consumed significant bandwidth and capital from the health systems and have not delivered on the promise of efficiency, effectiveness, and market power. More often than not, post-merger integration and synergy realization have been marginal. Instead of creating value, they resulted in value destruction. We have already started to see the negative impact of physician acquisitions by health systems becoming an economic liability versus asset. To create value from M&A activities, executives must ensure the deal will result in gaining or boosting capabilities required for strategy execution. The deal must close a capability gap. And cultural alignment and identity of the future enterprise should be front and center.

Complacency Does Not Promote Change

The recent market activities and pseudo vertical integration of payers into critical parts of the delivery system may act as a catalyst to speed up transformation for health systems, all of which are good business practices and no-risk, no-regret moves. Staying complacent may result in becoming marginalized and left behind. As many believe healthcare is the next frontier for major transformation, and redefining its boundaries in the 21st century is enabled by the promise of artificial intelligence, information technology, and beyond.

But changing the basics and building foundational capabilities is just a starting point to move toward quality and affordable care. The health systems that recognize this need to stay front and center. The time is now.