President Trump recently declared the opioid crisis a national emergency, signaling a new era in the fight against this deadly epidemic. The increased attention and commitment can’t come fast enough: There were 2 million people addicted to prescription painkillers in 2016 and over 20,000 deaths from overdose, representing an overdose rate that has tripled since 2000. While the effects of the epidemic are disturbing in their breadth, it is particularly concerning to see the disproportionate effect that the epidemic has had on one particularly vulnerable population: Medicaid beneficiaries.

A major factor influencing addiction within the Medicaid population is the sheer number of opioid prescriptions being written – 15 percent of Medicaid enrollees had at least one prescription opioid claim during 2012. Controlling prescribing can limit excessive opioid usage and encourage other methods of pain management. In this post we explore the cost and toll of the epidemic, as well as the different approaches that state Medicaid programs are using to monitor prescribing and next steps for Medicaid programs looking to address overprescribing.

Impact on Medicaid population

The cost of the opioid epidemic to Medicaid is large and growing. A 2016 CDC study estimates that opioid addiction cost Medicaid $5.5 billion between 2011 and 2012, including inpatient, outpatient, and prescription costs for individuals with clinically diagnosed addiction.

Meanwhile, spending on the drugs themselves came to $500 million for over 34 million prescriptions in the same year, representing 2 percent of all net prescription drug expenditures – and that’s just for fee-for-service Medicaid. With state budget cuts looming and a disproportionate share of Medicaid enrollees affected by the epidemic, state Medicaid programs need to find ways to prevent addiction and reduce associated costs. And the first step toward reducing addiction is to reduce the number of opioid prescriptions written in the first place.

How states are addressing overprescribing

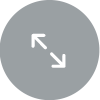

Many states are taking steps to track and control prescribing behavior around opioids. The below infographic describes some of the tactics and their prevalence across the country.

We have seen some demonstrated progress through these approaches, mainly with prescription drug monitoring program databases (PDMPs). But these efforts are still relatively new; and some states are left wondering whether these restrictions result in the best outcomes for their constituents, some of whom have legitimate need for pain medication.

A new approach to appropriate prescribing

Physicians are increasingly being asked for pain medication and some struggle to determine how to prescribe appropriately. It may be obvious that a patient needs some pain management after a procedure or while managing a painful condition. And it might be clear that an endless supply of opioids puts a person at high risk for addiction. But how much is enough? How much is too much? Three tablets? Six? 12?

Physicians are not the only ones grappling with this challenge, as the issue of appropriateness also is a problem for states. While many states have programs in place to flag physicians whose prescription rates are so egregious that their behavior is clearly unjustified, few have programs in place to identify areas of overuse among physicians who – in most other areas of their practice – are practicing in line with guidelines and peer-established norms.

In other words, state programs do not account for the complexity and nuance of pain management. How many pills should be prescribed for a given patient population after a given procedure? There is no clear answer, but comparing the prescribing behavior of physicians in the same specialty who are prescribing opioids to the same type of patient can help shed light onto what constitutes “appropriate” prescribing behavior.

Practicing Wisely™, a new initiative aimed at developing measures of clinical appropriateness, does just this. States can use the program’s opioid measures to track variation in physician prescribing behavior for specific cases of opioid use, such as prescription rates following a C-Section. Comparing physicians’ prescribing patterns to the prescribing patterns of like-specialty physicians, performing the same procedure on a similar patient population can help to identify physician outliers. That is, physicians whose prescription rate deviates constantly from the rates of their peers for a given type of opioid use. Importantly, physicians can gain insight into how their peers are responding to demand for opioids and can consider any adjustments to their own behavior that might be more in line with what is typical among a similar population.

To manage and (eventually) reverse the opioid epidemic, state Medicaid programs should now take a deeper look at the role prescribing plays, and they can tackle the “gray” area of appropriate prescribing through the deployment of appropriateness measures.