The European Green Deal aims to reduce CO2 emissions 55% by 2030. This will require the transport sector, which represents a quarter of the EU carbon footprint, to reduce emissions 70%. Shifting freight away from road transport and passengers away from air and car to rail is seen as a critical step in achieving this goal. Rail is already one of the greenest modes of transport, but before such a shift is possible, rail has a few problems to iron out.

The biggest obstacle for a major expansion of rail is congestion, which currently limits capacity on critical routes and creates bottlenecks. Rail also has a problem with punctuality, reliability, flexibility, and transit times, with the exception of the high-speed systems of Italy, Spain, and France, which hurts its competitiveness with other modes.

Building new infrastructure to increase service levels is problematic for several reasons: It would be extremely expensive, with many bottlenecks occurring in urban areas that simply lack the space for more rail. Planning and implementation can also take decades.

Oliver Wyman recently reviewed a new generation of technology, currently in development, that is designed to be added to existing rail infrastructure to improve capacity and flexibility. These technologies are designed to avoid the need to build either new conventional tracks or invest in massive new systems like hyperloop, offering the potential of lower cost and shorter timeframe to implementation.

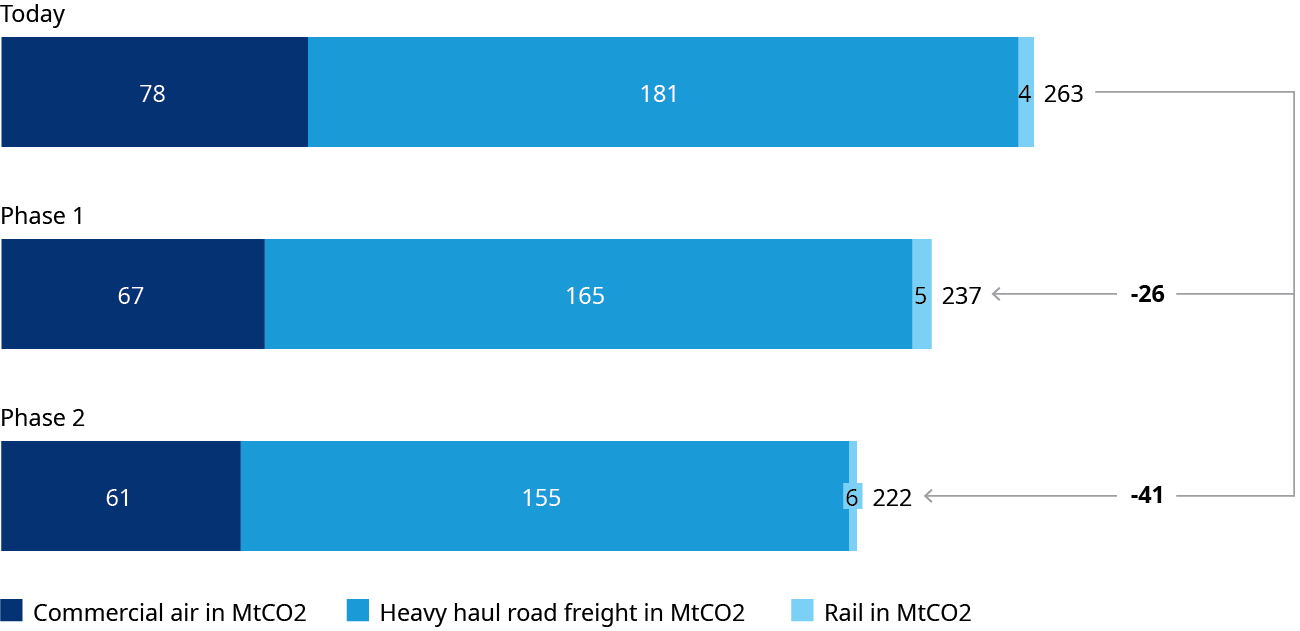

One technology being evaluated by several EU railroads and ports is passive magnetic levitation with linear propulsion. This involves components being added trackside and to existing rolling stock that would cause trains to levitate off the track (eliminating friction) when they get going fast enough. Oliver Wyman estimates that such a system could increase overall rail line capacity by 30% to 40%. A second phase, using lightweight, higher-speed vehicles (“pods”), could increase capacity by 55% to 65%. Speeds could also increase substantially, making rail a much more attractive alternative to air for travelers. And most critically, by shifting more transport to rail, transport-related CO2 emissions could be reduced by 26 million to 41 million tons per year.

Given the high stakes and the pressing timeframe for realizing the European Green Deal goals, Oliver Wyman believes that a joint effort of European operators, asset managers, and technology providers is needed to create a pilot program to test the potential of this new rail technology, with an eye to expanding it one day to some key network segments and corridors.

This is just one example of a possible shorter-term solution to European transport’s emissions problem. With impending deadlines on emissions reduction looming, Europe must decide soon how to make better use of its rail system.

Note: Overall demand will grow in the future but is assumed static in this study for better comparison.