Editor's Note: The following article, about our Future Truth predictions for the healthcare industry, was originally published in the Oliver Wyman Health Innovation Journal, Volume 4.

Climate change is a threat that looms large on the horizon – and yet it often seems to be a danger that will remain in the distance forever and will never catch up to us – until one day it does, just like COVID-19. Extreme weather events and trends such as higher temperatures and rising sea levels are raising the rate of death and disease, disrupting healthcare, and escalating costs. As climatic conditions move out of the “Goldilocks zone” in which species – humans included – evolved, the speed and scale of compounding effects may overwhelm societies, businesses, and governments around the world.

The health and life sciences sector is part of the problem: If the sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases on Earth due to the production, transport, and disposal of products and services across the life sciences supply chain.

However, this sector is also a crucial part of the solution: It has the opportunity to mediate the health impact of climate change, and to minimize the harm and inequities for patients, staff, and societies.

Health and economic disparities are magnified by climate change.

A Threat Multiplier

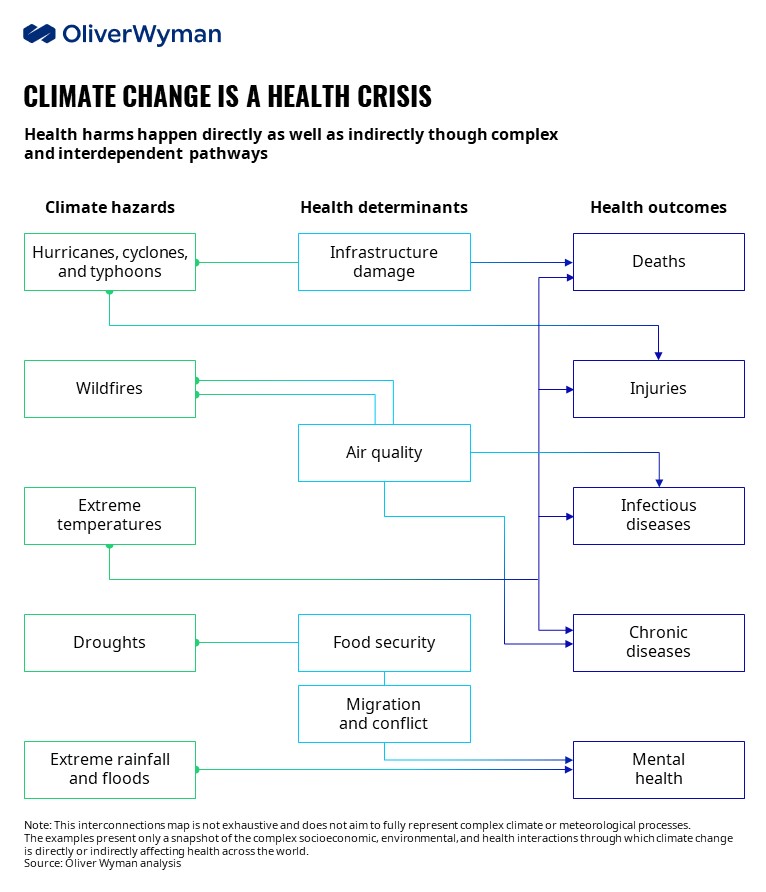

Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century. The below chart from Marsh McLennan Advantage’s Climate Health Threat Illustrator shows that the dangerous impact on health is complex and varied. Climate change will exacerbate the burden of every major disease category: infectious disease, chronic disease, mental health, injuries, and deaths.

Environmental events and trends harm people’s health directly and indirectly by altering complex and interdependent pathways — ones that are both natural and manmade (see exhibit). These pathways act as environmental, social, and economic determinants of health. For example, more frequent and intense storms can inflict more damage and injury – this is a direct result; they also can inflict more death by disrupting urgent and essential medical care – an indirect effect.

Climate impacts on health range from mild to severe and from acute to chronic. Wildfires and floods, for example, cause an initial spike in physical and mental health needs during each disaster, followed by a long tail of lasting poor health. Over time, this long tail amounts to multiples of the original surge in healthcare costs and productivity loss. Risks and outcomes once perceived as far off in time or space are unfolding. In time, they will intensify in both developed and developing countries.

Health and economic disparities are magnified by climate change, with the people and places the worst hit being least capable of coping. For example, the elderly, the poor, and people with pre-existing conditions face greater mortality risk during heatwaves. Rising temperatures and sea levels threaten both lives and livelihoods in tropical islands and regions, undermining their capacity to respond to catastrophes.

Climate Change is a Health Crisis

Health harms happen directly as well as indirectly through complex and interdependent pathways.

How Climate Change Impacts Health and Well-Being

Mortality risk will rise. More frequent and intense heatwaves will increase the risk of early death. Annual heat-related deaths could increase nine-fold in the US, from about 12,000 now to more 100,000 by 2100 in a high-emissions scenario. Besides the elderly, others at greater risk are children, the poor, and those with pre-existing conditions. As the planet warms, intensifying cyclones and hurricanes are likely to bring stronger winds and rain – and disrupt hospitals and other healthcare providers. In the three months after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, for example, one-third of casualties may have died because medical care was disrupted or delayed.

People will experience more injuries. Hotter days are likely to increase the risk of self-harm and interpersonal violence. Hypotheses as to why this correlation exists range from climate-induced resource strain to people’s varying psychological responses to heat. In a high-emissions scenario, there may be 9,000 to 40,000 more suicides in the US and Mexico by 2050, as well as an additional 3.2 million violent crimes in the US by 2100. Rising ocean temperatures degrade coral reefs that ordinarily dissipate energy from sea waves, weakening a natural defense against coastal erosion, storms, and floods in low-lying coastal areas. By 2045, in a business-as-usual scenario, severe coral bleaching could expose 26 million people across the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia to injuries during storm surges.

Infectious disease will pose a greater threat. Climate change and air pollution act as risk multipliers increasing the risk of infection and death from respiratory diseases such as COVID-19. In the US, a small increase in long-term exposure to fine particulate pollution (PM 2.5) is associated with an eight percent increase of dying from COVID-19. Rising temperatures are spreading existing diseases and releasing long-dormant plagues. Dengue could spread to the Southeastern US by 2050 as mosquito transmission zones expand from the tropics. Arctic heatwaves are thawing permafrost and could revive sleeping pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses that cause anthrax, smallpox, or the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Chronic disease prevalence and related vulnerabilities will increase. Pre-existing conditions (for example, diabetes) and common medications, such as Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, reduce the body’s ability to cope with heat. As populations age and heatwaves become common, people may become more susceptible to dehydration and heat-related illnesses. Consider, for example, that short-term heat exposure spiked the relative risk of heart attacks in Germany from 1987 to 2014 – particularly for diabetics. As fire seasons grow longer and more severe, chronic ill health and significant costs related to smoke exposure are surging. In 2019, for example, the Black Summer bushfires affected 80 percent of Australia’s population. Premature deaths and hospital admissions accounted for more than half of the total costs of the fires. Survivors may face an increased risk of cancer as well as respiratory and heart disease.

Mental health issues will become more prevalent. Extreme weather can result in lasting mental illness. After severe flooding in England in 2013, for example, an estimated 37 percent of affected households suffered from anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress; public health and welfare costs are estimated to have topped $32 million. These symptoms can persist for years. Droughts, floods, hunger, and poverty are triggering forced migration from Central America’s Dry Corridor, for example, with migrants who are exposed to violence at home or in transit, suffering psychological impact. Some 56 percent of migrants screened in Mexico, for instance, had either moderate or serious symptoms of anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress.

Annual heat-related US deaths could increase 9X between now and 2100 in a high-emissions scenario.

Reducing Carbon Footprints and Building Resilience

The health sector both contributes to climate change and must address its consequences: essential and elective care demand swings, diminished site and staff capacity, and cost pressures that threaten long-term viability. Health and life sciences organizations face physical risks of climate hazards (such as disrupted operations and supply chains); transition risks from rapid policy, technology, or market changes (including cuts in healthcare spending); and liability risks (for example, for poor health outcomes).

Yet the health sector – like other sectors – has been slow to mitigate and adapt. It has historically perceived impacts to be distant, complex, or uncertain, and has deferred systemic change. Providers, payers, governments, and employers must ensure essential health services and products remain available, affordable, and accessible to all who need it; policymakers, meanwhile, must pursue low-carbon policies and strengthen health systems.

To reduce health risks and costs for the communities they serve, health and life sciences organizations must begin by reducing emissions and building resilience. There are solutions providers, payers, life sciences, employers, and policymakers can adopt to drive meaningful and lasting change.

Providers: Lead by Example

Providers – hospitals, clinics, care facilities, and laboratories – have a large carbon footprint, with emissions coming from energy use in operations and supply chains. As climate change accelerates, providers face demand swings, diminished capacity, and financial stress. Specifically, providers will experience spikes and swells in the need for urgent and essential care due to acute and chronic climate hazards; disrupted or reduced capacity as climate hazards impair staff, supplies, and facilities; and lastly, delayed or forgone elective care, which poses an increasing health risk for patients and a financial strain for providers.

To cut emissions, providers must decarbonize facilities and supply chains where possible. For example, they must become energy-efficient, switch to renewable sources of energy and supplies, minimize waste, avoid unnecessary care, and use low-carbon technologies like telemedicine.

The health sector both contributes to climate change and must address its consequences.

Providers can also alleviate the health impacts of climate change in their communities. One way is to ensure continuity of care both during crises and in the long run by investing in climate-resilient facilities and technologies, sourcing from green supply chains, and devising flexible staffing and service models. Another way is to enhance community resilience by supporting public health measures to improve well-being and equity. A third way is to lead on climate solutions: to inform, engage, persuade, and partner with patients, staff, and other health sector stakeholders to promote climate action and prepare for health impacts.

Payers: Take a More Holistic Approach

Payers – health insurers and governments – face asset and liability pressures, as well as reputational risks. Climate change makes investments more volatile, particularly those in high-carbon sectors or those with significant exposure to physical risks. Claims may become unpredictable and unmanageable as costs soar due to health crises. Public payers serving older, poorer, and more vulnerable populations will face severe cost pressure. Rising premiums will widen the already large health protection gap and increase reputational and regulatory risks for private insurers.

Life Sciences: Prepare for a Changing Disease Burden

Pharmaceutical and life sciences companies, in particular, face pricing and patent challenges – pressures that add to the challenges and pushback from payers, providers, and patients who are all feeling the pinch as climate hazards increase the cost of healthcare. Plus, pharma and life-sciences companies also face “physical” risks such as disrupted operations and supply chains and transition risks from policy and technology changes.

Employers: Protect Your Workforce

Employers face greater risks to workers’ health and safety, thereby raising healthcare costs and lowering productivity, as climate change amplifies current health risks and introduces new ones.

Both indoor and outdoor workers may be exposed to heat, air pollution, or extreme weather at work. And, low-paid and migrant laborers can be especially vulnerable to these kinds of health risks.

Policymakers: Promote Steps Toward Resilience

Policymakers face varied and complex threats to public health from climate hazards, including: deteriorating determinants of health, increasing healthcare needs and costs, growing inequalities in health, intensifying geopolitical tensions from climate migration, and the financial burden of being lenders and insurers of last resort.

The health sector must strike a balance between efficiency and resilience.

All Stakeholders Must Reduce Their Carbon Footprints

The health sector must strike a balance between efficiency and resilience, cutting emissions and costs without sacrificing preparedness. All stakeholders have room to assess and reduce their climate-related vulnerabilities, and to encourage and incentivize others to go green. Some changes will increase efficiency and resilience: For example, clean energy and low-carbon technologies can reduce emissions, protect public health, and keep health services running through crises. Other options present trade-offs, such as just-in-case capacity and stockpiles of essential supplies that boost resilience but also costs, resources, or emissions.

Payers: Here are four solutions for payers to help societies understand, reduce, and cope with climate-change health risk in a more holistic manner. First, curb emissions in operation and channel investments into green assets. Second, incentivize healthcare to go green – for example, by preferring sustainable providers, developing policies to reduce unnecessary care, reflecting climate risks in pricing, and/or encouraging risk reduction. Third, payers can reduce health impacts and inequities by developing products/models to ensure universal access to affordable prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, and by taking a holistic approach toward improving key health determinants, such as food and housing. Finally, payers must ensure operational and financial resilience by providing adequate and sustainable coverage to everyone who needs it. Working together, public and private payers can pool risks and limit losses more effectively and equitably.

Pharma and Life Sciences: Pharma and life sciences companies have opportunities to reduce their carbon footprint. First, curb emissions: reduce energy use, switch to renewable sources of energy and supplies, minimize waste, and invest in low-carbon technologies and techniques such as green chemistry. Second, make supply chains more resilient: reconfigure suppliers to account for emissions and vulnerabilities to climate and political or regulatory shocks. Third, prepare for a rapidly changing disease burden: align product pipelines (such as medications for tropical diseases or heat-related illness), and invest in rapid response capabilities and partnerships (for example, to repurpose drugs, devise tests, or discover vaccines for new infections). Lastly, reduce health impacts and inequities: prioritize affordable innovation and essential products including antibiotics and antivirals.

Employers: Besides reducing their carbon footprint, there are four ways employers can reduce workers’ vulnerability to climate impacts: first, monitoring climate-related risks to physical and mental health; second, mitigating risks through training and changes to work sites, schedules, practices, and equipment (such as climate-resilient buildings and personal protective equipment); third, ensuring there is guidance and support for affected workers; and fourth, improving socio-economic determinants of health (such as financial resilience). As payers, employers can design and select health benefits to promote sustainable healthcare delivery and increase workers’ resilience to climate events.

Policymakers: To minimize health impacts, policymakers should drive mitigation and adaptation efforts in the following ways: First, make “no-regret moves” such as low-carbon policies that promote clean air, water, housing, and transport, as well as healthy food and physical activity. Second, strengthen health systems by investing in resilient infrastructure, equipment, workforce, and supply chains; ensure sufficient supplies of essential products; and reward sustainability measures. Third, build national and community resilience by integrating direct and indirect health impacts into disaster planning and risk reduction. Fourth, ensure effective crisis response by monitoring climate trends and health impacts. Lastly, spur investment and innovation now to avert or respond to crises rapidly.

One of COVID-19’s lessons has been the cost of inaction and the value of preparedness, prompt response, resilience, and coordination. Given the clear links from climate to health harms and the lag between emissions and consequences, urgent action is vital. The right responses today will go a long way toward reducing risks and the need to make even more drastic and expensive changes tomorrow.

.jpg)