In an earlier post, we provided results showing how, in our opinion, the CMS-operated risk-adjustment system contributed positively toward the intended objective of allowing issuers to compete in the non-group market on bases other than risk selection. We drew that conclusion from our analysis of risk-adjustment results for 2014. The new draft Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters (NBPP) provides states with the option of altering the risk adjustment payment transfer formula by reducing payments and receipts in the small group market by up to 50 percent, beginning in 2019.

In this post, we update our earlier post using data from 2015 (the most recent available), we include an analysis of risk adjustment in the small group market, and we use the 2015 data to show the effect on results if the states had opted to alter the payment transfer formula by reducing transfers by 50 percent in 2015 as allowed in the draft NBPP.

We reach the following conclusions:

- As was the case in 2014, in 2015, the risk adjustment system was helpful in allowing plans to compete based on features other than risk selection.

- If the transfer formula for the small group market had been adjusted in 2015 as allowed for in the draft NBPP by reducing payments and receipts by half, the system would have performed less well in compensating health plans with costs in excess of what we have calculated as the statewide average.

Risk-Adjustment Receipts Versus Distance from State-Wide Average Claims in the Non-Group Market

The risk-adjustment model operates at the state-wide level. In Chart 1, we show how an issuer’s risk-adjustment receipts in the non-group market varied with claims relative to the state-wide average claims in 2015. Those issuers with claims that were higher than the state-wide average were more likely to be recipients of risk-adjustment payments (R2 = 0.62). In essence, as was the case in 2014, in 2015 the risk-adjustment system tended to bring down the cost of claims for plans with high claims per member per month (PMPM) and bring up the cost of claims of plans with relatively low claims PMPM.

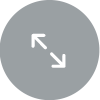

Risk-Adjustment Receipts Versus Underwriting Gain in the Non-Group Market

In Chart 2, we show how risk-adjustment receipts PMPM in the non-group market varied with net underwriting gain. (In calculating net underwriting gain, we included risk-adjustment and transitional reinsurance payments, but excluded reported payments under the third premium stabilization program, risk corridors, due to a lack of funding for this program.) Based on the least-squares line included in Chart 2, underwriting gains are not correlated with risk-adjustment payments PMPM in 2015. This finding is consistent with the data from 2014 and suggests risk-adjustment has a much larger effect on normalizing claims to a state-wide average level than on an issuer’s profitability, and that factors other than the payments or receipts under the risk-adjustment system are more likely to be driving issuers’ underwriting results.

We have developed small group market charts that are similar to the preceding non-group charts. In creating these charts, we limited the analysis to six states (Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Michigan, Montana and North Dakota) where the number of reported member months in the MLR data that we use as the basis for this work is at least 90 percent of the reported billable member months in CMS’s “Summary Report” on risk adjustment transfers.

The risk corridors column of the MLR reports the source of data for this analysis includes all ACA-compliant business for issuers participating on the SHOP. However, in the small group market, there are many issuers who are not on the SHOP and who, therefore, do not report their experience in the risk corridors column of the MLR reports.

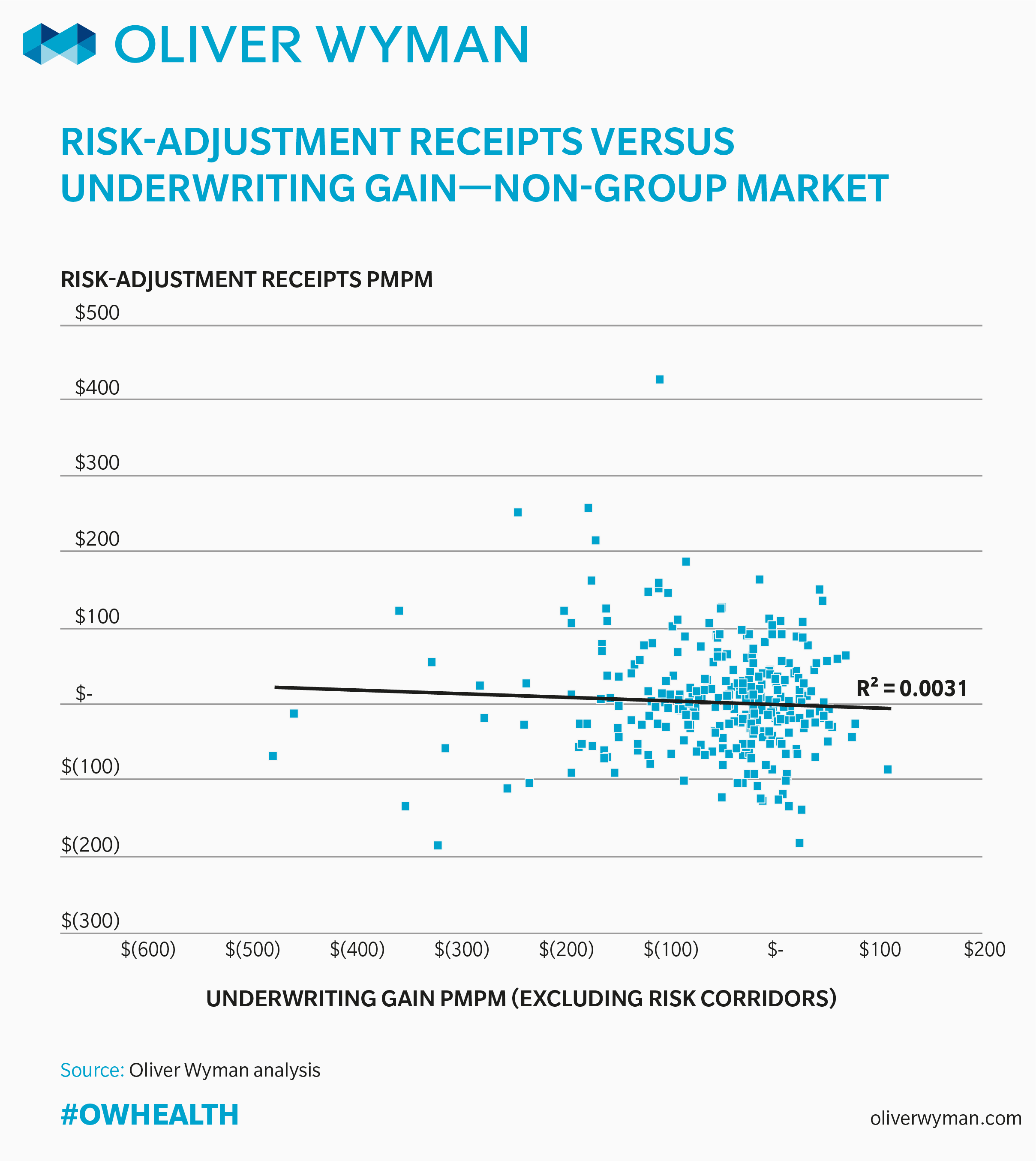

Risk-Adjustment Receipts by Distance from the State-Wide Average Claims in the Small Group Market

In Chart 3, we show how an issuer’s risk-adjustment receipts PMPM in the small group market varied with claims PMPM relative to the state-wide average in 2015, again, for those states where we had more than 90% of the ACA-compliant market represented in the MLR data. As was the case with the non-group data, there is strong correlation between an issuer’s claims PMPM relative to the state-wide average and that issuer’s receipts under the risk adjustment system (R2 = 0.50).

We have also included the equation of the least-squares line. The slope of the line is 0.43. If the slope of the line was 1.00, it would mean that for every $1.00 PMPM an issuer was above (below) the state-wide average, they received (paid) $1.00 through the risk-adjustment system in 2015. The slope of 0.43 means that issuers received (paid) $0.43, on average, through the risk adjustment system for every $1.00 they were above (below) the state-wide average. We believe this is evidence the risk-adjustment system is playing an important role in allowing plans to compete based on features other than risk selection.

As we said at the outset, the draft NBPP gives states the option, beginning in 2019, of adjusting the risk adjustment payment transfer formula to reduce by half the risk adjustment payments and receipts. The practical impact of this in 2015 would have been to lower the slope of the line in Chart 3 by half, so that on average, issuers would receive (pay) only $0.22 PMPM for every $1.00 they were above (below) the state-wide average, lessening the effectiveness of the system to compensate plans with high-cost enrollees, and increasing incentives for plans to attract healthy enrollees and avoid those likely to require significant medical care.

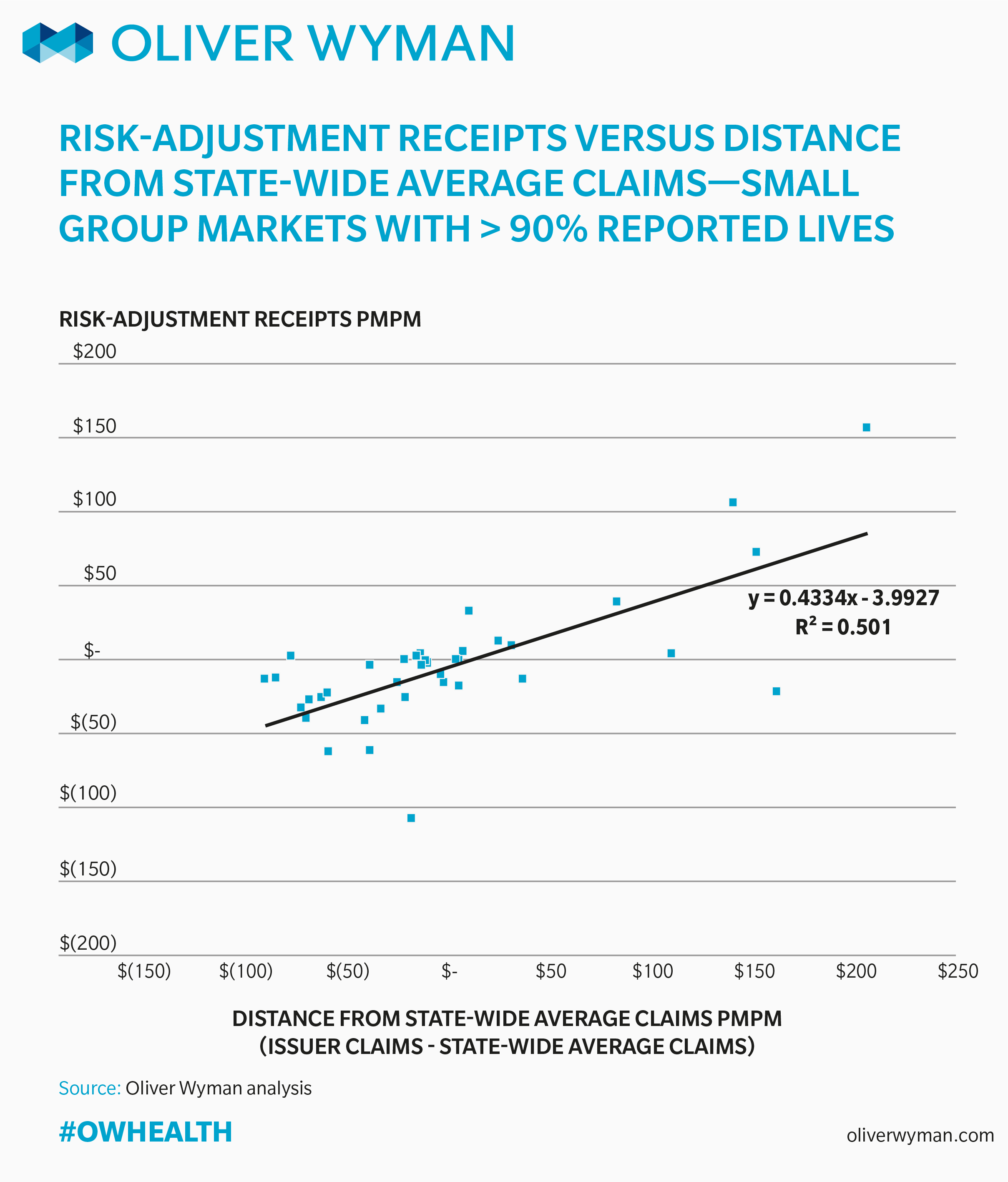

Risk-Adjustment Receipts Versus Underwriting Gain in the Small Group Market

In Chart 4, we show issuers’ risk adjustment receipts relative to their underwriting gain in the small group market for the states where the data in the MLR reports represents at least 90 percent of the ACA-complaint market. As was the case in the non-group market, in the small group market, the poor fit of the least-squares line (R2 = 0.11) indicates factors other than the size of an issuer’s risk adjustment receipts or payments seem to be driving underwriting gains.

While there are clearly outliers in the data, from a system-wide perspective, the CMS operated risk-adjustment system appears to have worked as intended in 2015 in the non-group and the small group markets, transferring funds from plans with relatively low risk to plans with relatively high risk.

A Word on Data

The results as presented make use of the data as reported by issuers in their MLR reports. We did not audit or validate this data. It is not possible given the data available to adjust the data for differences among issuers in provider contracts and reimbursement levels, care management capabilities, issuers’ efforts related to managing the risk-adjustment process, or a number of other characteristics of the issuers’ business that could have an impact on the results.

In addition to the state flexibility described above, the risk-adjustment system will be different in 2019 than it was in 2015 with different coefficients, adjustments for policyholder duration, the inclusion of prescription drug information, and an adjustment for administrative expenses. For this and other reasons, the results from 2015 may not be representative of results in the future.

The data used in this analysis is available here. In developing these charts, we excluded issuers in a state if they had less than 12,000 member months in that state to remove excess variability from the results. We also excluded issuers from Massachusetts (because Massachusetts operated its own risk adjustment system in 2015), West Virginia (because there was only one issuer operating in the state), and Vermont (due to its merged market).