Editor's Note: This article was originally published in the Oliver Wyman Health Innovation Journal, Volume 4.

Competition between healthcare providers traditionally has been static and predictable. Organizations have tended to rely on beating rivals on the basis of a strong presence on the ground and consumers’ interpretations of clinical brand quality. That is, until now. The new basis of competition between care delivery organizations is shaping up to look very different. This is because of rapidly evolving care delivery needs and the need to "catch up" to what consumers want versus what they're being offered. Players will (mostly) win on ease of use, price, and supporting people to live healthier lives, rather than winning because of an overwhelming local presence and consumers’ fuzzy notions of quality.

Technological advancements have revolutionized medicine in recent decades. Procedures that could only have been imagined in the past – for example, the use of DNA to guide care decisions or minimally invasive procedures – have become commonplace, with patients enjoying their benefits. And providers’ operations have also benefited from improved record-keeping, administration, and billing.

At the same time, however, the consumer experience has seen little improvement. Access to care, overall, remains constrained, and scheduling care is predominantly analog – phone calls with elaborate voice menus are common when trying to access care, for example. Moreover, the nature of care continues to be reactive, patient-driven, and conducted in response to illness.

The consumer-centric healthcare revolution – long predicted – has yet to materialize. However, a tipping point is now within sight. Enhancing the consumer care delivery experience and supporting people to be healthier will become the dominant key to success. Below, we outline some traditional means of differentiation and how new factors centered on enabling a better consumer experience will become the dominant themes in the future.

Local Density and Perceived Quality

Traditionally, competition between healthcare players has focused on two key elements:

Local availability: Creating a robust network of brick-and-mortar care locations predicated on primary and specialty-care offices and revolving around a local acute-care hub such as a community hospital.

Clinical brand and quality: Communicating and convincing consumers that clinicians who are employed by a health system are highly trained, highly capable, and are delivering error-free, effective care. This includes showcasing clinical superiority capabilities (such as a new surgery technique or cutting-edge instruments), with the belief that these positively impact all other services. It also includes competing on the latest advanced technologies or equipment. Consider, however, that a reported 59 percent of consumers tend to focus on doctor-patient relationships and personality versus 29 percent who tend to focus on care delivery or outcomes.

Of note, a small number of institutions have transcended the limitations of local geography and have been able attract patients from across the nation and the world. The Mayo Clinic is one such example. Similarly, some innovative plan sponsors (such as Boeing, Pepsi, and Walmart) have been identifying national-level centers of excellence and diverting their employees/members there. Still, the bulk of care delivery competition is happening within the context of a confined locale.

Drivers of Change

In recent years, however, macro and industry dynamics have begun threatening to upend the traditional basis of competition:

- People’s experiences with other consumer-facing industries have set the bar high for what they expect from healthcare providers (for example, timely access to services). Similarly, a generation of more-educated consumers, with greater and faster access to information and resources than ever before, has come of age.

- Increased costs have caused plan sponsors and consumers to scrutinize and favor comparable lower-cost care options (such as stand-alone imaging sites or ambulatory surgery centers).

- Employers have been addressing cost concerns by shifting more cost responsibility over to employees.

- This staggering increase in consumer financial responsibility has shifted patient behavior, forcing them to act more like informed customers.

- Finally, clinical advancements have allowed care to be delivered in less specialized settings, making it more accessible. (Consider, for example, the shift from tertiary to community, from inpatient care to hospital outpatient departments to ambulatory surgical centers, or from offices to homes).

This Time is Different

In recent years, we have both seen and made predictions regarding the basis of competition for care delivery – forecasts that didn't materialize. So, what makes this time different? Three specific factors are at work currently.

First, payers have been vertically integrating. They are looking to control the key elements of care delivery that influence the total cost of care (for example, primary care). CVS-Aetna’s Health Hubs, Optum’s ownership of physicians, and various Blues launching care delivery assets are just some examples. All are adding access points that emphasize convenience, price, and an integrated health experience.

Second, the digital care model has been quickly adopted as a result of COVID-19. (For example, the rate of private-insured medical claim lines associated with digital care have jumped nearly 40-times fold in March 2020, compared to 2019.) This shift has introduced the public to the possibilities of a care model that’s location-agnostic and virtual-first, with required physical interventions rounding out clinical care rather than being the default. Indeed, nearly 60 percent of people who used telehealth for the first time during the pandemic (or increased their usage) said that they will continue to use telehealth once stay-at-home orders are lifted. (See Chart below.) Moreover, even before the pandemic altered the landscape, we had observed that once consumers try digital care, they generally find it appealing.

How frequently will you use telehealth once stay-at-home orders end?

Source: Oliver Wyman

Third, the unstoppable pace of technology development (including cloud computing, the Internet of Things, processing power, bandwidth, and wearables) means an “always on” approach to healthcare is a real possibility. This approach is centered on proactive monitoring and real-time engagement, thus diminishing the importance of the provider visit. Technologies such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and Apple Watch’s cardiogram were early examples of this proactive, real-time approach. More recently, discrete information flows are being aggregated to create a 24/7 picture of health. (Consider, for example, Propeller’s asthma inhaler that uses sensors to track your medication use, or Pillsy, which sends patients smart medication reminders when they forget a dose.) In the future, business models embodied in the recent Teladoc-Livongo deal, for example, are expected to leverage these possibilities.

Four Features of a New World

A new basis for competition. Over the next decade, we believe that as a result of some of these trends, players will compete on a different set of attributes than do they today. Moreover, the recent adoption of virtual and digital care is only just beginning. So far, providers have been taking their legacy care models and making them virtual. There remains significant headroom to reinvent care delivery – primary, secondary, and even tertiary care – that is untethered to a physical modality.

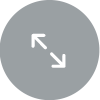

Evolution of a Care Delivery Ecosystem in a Commoditized/Democratized Healthcare World

The basis of competition will thus shift from having a strong physical presence and clinical brand to ease of use, experience, and cost. Technology will open up local markets – traditionally insulated from external forces – to be part of a national, even global, marketplace where players will compete for consumers’ and plan sponsors' wallet share.

It’s important to note the shift of strategic control away from local presence and clinical brand perception has already begun in parts of the care delivery continuum. For example, urgent care is no longer controlled by traditional primary care, as a plethora of physical and virtual options have sprouted up. And access to behavioral health is being democratized with app-based services such as AbleTo. We expect other segments of care to follow suit, where interactions are primarily about information exchanges rather than a laying on of hands – for example, a greater future focus on disaggregating specialist consultations from surgery.

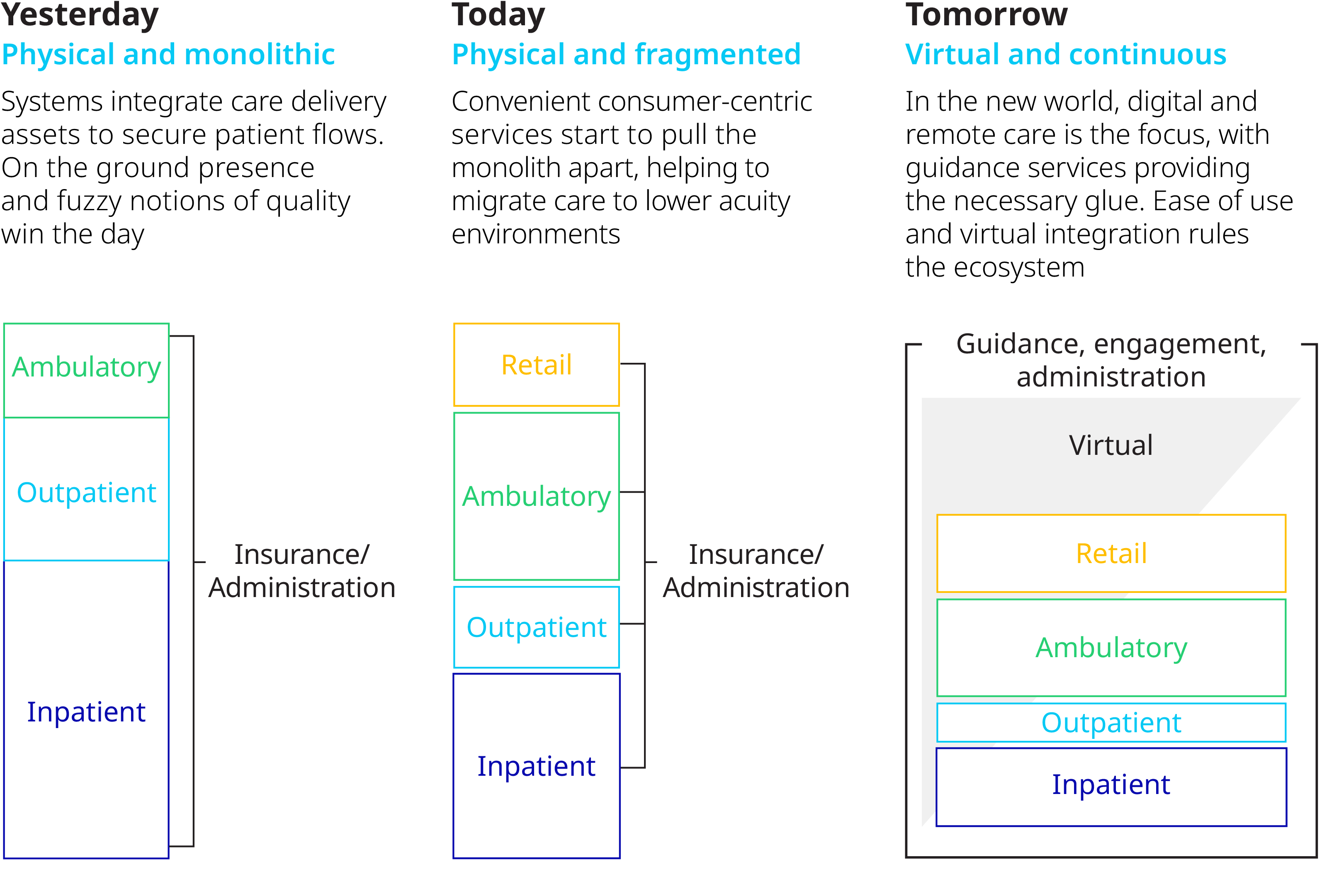

A new taxonomy for care delivery. We predict this trend of reclassifying care will continue and ultimately envelop many clinical use cases – except for truly cutting-edge clinical innovations. This will cause a redefinition of the traditional primary-secondary-tertiary hierarchy of care, which lends itself to accept clinical specialization as the yardstick for care delivery. Instead, consumers will come to think of care delivery in terms of a hierarchy of modalities. This hierarchy will start with self-service as a default, continue with artificial intelligence/bot-led interaction, and only later be followed by a clinician interaction. This clinical interaction will take place initially as a virtual visit, with a physical and appointment-based visit happening almost as a last resort.

The Consumer Experience Across the Care Continuum

New care models. We also believe care models will evolve from reactive and open-ended to proactive and closed loop. Providers will make use of massive, ongoing information flow that is fed, processed, and analyzed automatically to detect and alert required human interventions – instead of waiting for the person to present with symptoms or leaving it to chance that the patient will follow through on the care instructions they have been given. As the models progress, data collection and inputs into the care continuum will increase – beyond just consumer self-reported data, episodic consults, or scans. As technology advances, wearables and remote monitoring proliferate, data will drive improved clinical outcomes and redefine encounter-based care models. And because care was triggered on-time (or even, preventively) rather than through a person realizing he or she is suffering or is experiencing an acute event, the intervention will become far more personalized and contextualized to the individual’s needs.

It’s important to note that not all care that can be digitized will automatically become a virtual experience. Some consumers will still favor physical interactions even when comparable care can be delivered virtually. However, access to care will become consumer-driven: on-demand and at the modality of their choice, such as office, retail, home or digital.

New workforce competencies. When technology allows clinicians to intervene only with individuals requiring their attention, and when consumers can access self-service tools such as care bots, panel size can increase. However, clinicians will need to relearn key portions of their training – for example, Review of Symptoms (ROS) – now processed and presented to them by an electronic system first. The nature of clinicians' employment, recently reimagined as a work-from-home job during COVID-19 and enabled by the thirst for talent by telehealth companies – may be reinvented, with a meaningful part of the workforce opting for an independent contractor status that allows them greater scheduling flexibility.

The implication of this new world is that even players with strong clinical advantages should consider their ability to attract consumers in a future where the consumer is routinely cared for in an integrated, easy to use, and cost-effective way. In this future, those players that own consumer loyalty will influence downstream care decisions via referrals and recommendations, thus making tertiary-care providers more dependent on them.

We foresee the deciding factors of providers’ business models undergoing a sea change. Instead of the traditional local presence and perceived clinical quality, a new type of provider organization will emerge – one that will succeed based on its ability to serve consumer needs and that will leverage digital capabilities as an integral part of its care model. The onus is on incumbents to adapt to this new environment.