The Biden administration announced a new accountable care model two weeks ago, marking the first big release to advance on the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s revised strategic priorities. The ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health model launches in January 2023. Advanced planning will be critical for providers seeking to move into the new program.

Key Factors for Providers and Provider-led-ACOs to Understand

The Geo Direct Contracting model is scrapped, and ACO REACH is replacing GPDC. The controversial Geo model, launched during the Trump administration, was going to allow traditional and non-traditional risk-bearing entities to take on risk for lives across an entire market beyond the normal attribution method for other ACO models. The Biden administration paused the program due to complaints from a variety of stakeholders and its permanent cancellation occurred the same day as the ACO REACH announcement. While this is likely a disappointment to Medicare Advantage-focused organizations looking to find new ways to broaden their footprints, these players will still have a route to supporting value in Medicare in the ACO REACH model.

The Global and Professional Direct Contracting models are technically being retired and replaced by ACO REACH. Existing GPDC participants will be transitioned into ACO REACH and have until the end of the year to become complaint with the new regulations.

A new incentive will help to address health equity. This is one of the more notable changes and signals action on CMS’ declared priority to improve health equity. A new benchmark adjustment was added to positively incentivize ACOs covering underserved communities and beneficiaries — or at least avoid inadvertently penalizing them for doing so. In announcing the new model, CMS noted research has shown that underserved communities underutilize services relative to need, which creates a disincentive for ACOs to cover underserved areas; this model aims to flip that disincentive.

Adjustments will be made at the beneficiary level using dual-eligibility status and the University of Wisconsin Area Deprivation Index based on census block of residence. The dollars in play at the beneficiary level are potentially material — $30 per beneficiary per month lift for bottom decile beneficiaries and $6 per beneficiary per month dampener for top decile beneficiaries. However, as these are netted out across a population, CMS estimates this will have a marginal impact on most ACOs, with only a +/- 0.2% change in the benchmark. CMS estimates ACOs with the highest percent of underserved beneficiaries may see upwards of 1% change in the benchmark.

Limits on increasing coding intensity have both a give and a take. Two modifications were made to the symmetric 3% cap on changes to the population risk score. The “give” is that the 3% cap will not include changes to the demographic risk score. So, if the covered population is aging, the net flexibility for risk score changes is higher. The “take” is the adoption of a static reference year population starting in 2024, which will be more limiting to changes in coding intensity relative to a rolling reference year population.

Governance must be provider-led, with an opening for exceptions. At least 75% of the voting rights of the ACO’s governing body must be held by Participant Providers. Previous rules allowed this be as low as 25%. The door is left open though to accommodating a lower threshold for ACOs that submit proposals detailing the current governing body and ways Participant Providers will be involved in governance. Additionally, the Medicare beneficiary and consumer advocate serving on the ACO’s governing body are no longer allowed to be the same individual.

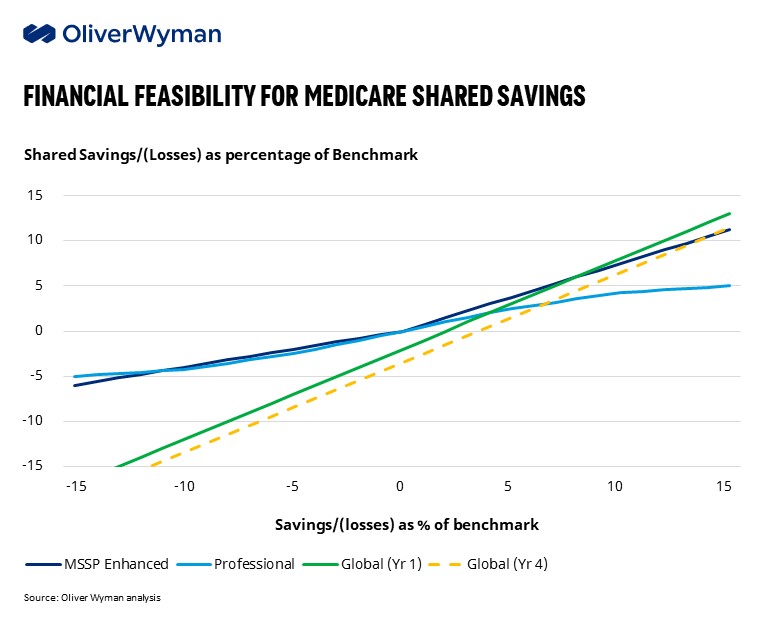

The benchmark discount is reduced, raising the savings retained by ACOs. The discount for the Global risk-sharing option drops from 5% in the outyears to 3.5% — nominally above the allowance for risk score coding accuracy improvement. This brings the discount in-line with our estimates for ACOs to reasonably obtain long-term financial feasibility in this model. However, this still presents financial hurdles for ACOs to consider as they are comparing MSSP Enhanced, Professional, and Global risk options.

Major trade-offs remain for those considering ACO REACH versus MSSP Enhanced Track. Two factors will bear heavily on this decision. First is understanding how the ACO’s starting benchmark is impacted by its historical performance relative to the region (via the MA rate book). Second is the ACO’s expected ability to reduce total cost of care, recognizing that REACH offers an additional powerful lever of contracting with downstream providers and ancillaries. ACOs expecting to drive more than 7% reductions in TCOC in the first few years and more than 12% in the outyears will benefit more from ACO REACH. For those concerned about the high hurdle rate in REACH, there is also an option to start in REACH’s Professional track and shift into Global within two years. Beneath these top considerations, ACOs should consider the added administrative cost inherent in REACH, role of voluntary alignment in driving growth, impact of regional trends on difficulty of success, opportunity for earning in the High Performers Pool, cashflow timing, and benefit allowances to reinforce clinical impacts on TCOC.

Additional Noteworthy Changes

- The quality withhold will be reduced from 5% to 2% from PY2023 through PY2026. This limits the risk for ACOs with lower quality performance on the ACO REACH metrics and improves provider cashflow in-year. However, this also limits the upside for top performers receiving extra incentives from the High Performers Pool.

- Starting in PY2023, the optional stop-loss arrangement will have an attachment point which will be risk-adjusted to more accurately cover the cost of beneficiaries in excess of the predicted spending. For larger ACOs willing to take on the risk of high-cost beneficiaries, it may be worth waiving the optional stop-loss arrangement.

- Participant Providers in ACO REACH cannot participate in overlapping programs, including: Primary Care First, Independence at Home demonstration, Kidney Care Choices model, Vermont All-payer model, Maryland Primary Care Program, and Medicare Shared Savings Program.

- Health equity provisions require participants to implement a plan to identify and address health disparities. The provisions also use patient benefit as a lever to expand nurse practitioners’ scope of practice without physician supervision (e.g., allowing the NP to certify patient’s need for hospice care, establish/review/sign a home infusion plan of care, order/supervise cardiac rehabilitation, refer for medical nutrition therapy).

Expect More Changes on the Horizon

The last few years have been a rollercoaster of announcements in CMS programs, and we remain in a transition period. Every administration tries to put its own stamp on alternative payment models, but there’s been a consistent push over the past decade to move further away from fee-for-service reimbursement and grow value-based models. Yet, few value-based programs under CMMI have produced reductions in spending or improvements in quality. The Government Accountability Office and MedPAC have chimed in on the need for CMS to reduce confusion and duplication that runs across some of its alternative payment models. These programs remain far from maturity, but CMS is actively considering the longer-term glidepath.

To make these ACO programs sustainable, several key issues must be remedied:

- There are too many programs and they don’t always fit well together

- Programs must generate material savings to the government to be sustainable, yet have failed to do so in aggregate so far

- The benchmark reset is unsustainable for providers

- Aggregate shift of risk will continue to be tepid while it is fully optional

- Program flexibility to provider circumstance (size, financial resilience, prior value performance) is low

- Setting a proper benchmark faces different complications when the ACO program is small versus when it is at high scale

We look forward to seeing how these take shape to support moving our industry to a more sustainable system.