Editor’s Note: Organizations both in and out of healthcare seek to strengthen their consumer loyalty and relationships. And empathy in medicine is gaining increased importance for the healthcare industry. Empathy is also considered a critical factor in ensuring that people and populations remain healthy. For example, patients treated with empathy are more likely to share relevant information about their medical conditions and adhere to their treatment plans. To learn more about how clinicians can improve communication and practice greater levels of empathy in everyday practice, Jacqueline DiChiara, Editor, Oliver Wyman Health, chatted with Gregory Makoul, PhD, MS, CEO of PatientWisdom (now part of NRC Health) about humanizing the patient experience and turning healthcare transactions into meaningful relationships for patients and clinicians alike.

Jacqueline: PatientWisdom seeks to help clinicians understand what matters to their patients. Tell us more about your business model to address physician-patient communication challenges.

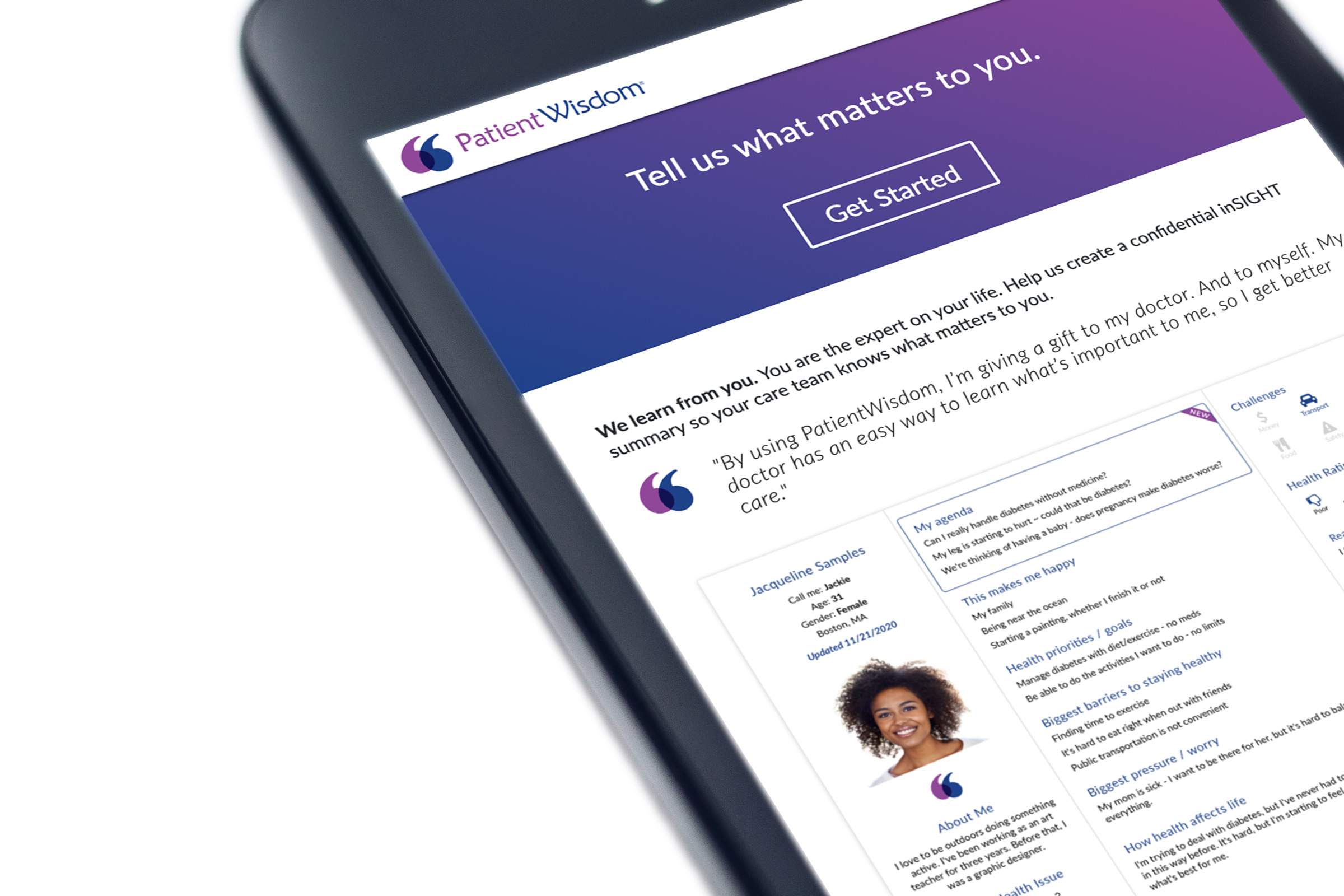

Greg: We built a HIPAA-compliant, mobile-responsive website that makes it very safe and easy for patients to share what we call “stories” about what matters to them – essential information about themselves, their health, and their care. We boil that information down into a one-screen view that clinicians access through the electronic health record (EHR). Any member of a patient’s care team can review this “inSIGHT summary” in about 15 seconds before going to see the patient, whether in-person or virtually. It helps them do even better without taking longer – better in terms of both communication and empathy – which drives value for patients, clinicians, and health organizations. We work with health system partners on a subscription basis.

Jacqueline: Before you started PatientWisdom, you were a communication scientist who became a full professor of medicine at a major medical school and then joined a health system as Chief Innovation Officer. You’ve done a lot of research on communication in healthcare. How should people be thinking about empathy?

Greg: When I was at Northwestern, we did some foundational research on empathy in everyday clinical practice. While empathy is often talked about or written about as an expression of shared feeling or experience, this is a very rare form, evident in only 2 percent of the encounters we studied. We asked patients how they think about empathy, and the clear focus was on feeling heard, which our studies delineated as Acknowledgement (I hear you), Pursuit (I hear you and want to know more), and Confirmation (I hear you and what you’re feeling/experiencing is valid). Feeling heard is a reasonable and realistic expectation, and part of our mission is to help make that happen on a regular basis. It’s no accident that the PatientWisdom tagline is “We hear you”.

"The patient is not the illness. The patient is not the chart. Each patient is unique."

Jacqueline: How does the PatientWisdom “inSIGHT summary” provide clinicians with a deeper, more personalized understanding of a patient’s needs and health goals?

Greg: It shows the clinician who patients are as people, what's important to them, and where they are on different style and preference meters that we generate out of what they’re telling us. The inSIGHT summary helps clinicians visualize the clinically valuable contextual information that they can use to make care work better. At root, we focus on humanizing both the experience and the delivery of care just by listening to the people that are involved in it. I think of this as radical common sense – we can all do a better job if we know what the people we are trying to help are trying to achieve.

The patient is not the illness. The patient is not the chart. Each patient is unique in terms of goals, challenges, and how health affects life in general. It's more likely that care is going to be effective if care teams see health in the context of a patient's life.

Even primary care physicians who have long-standing relationships with many of their patients tell us that although they’ve known a patient for a long time, seeing what that person shares in PatientWisdom opens a whole new way of thinking about care: “Oh, now it makes sense.”

Jacqueline: Do you have a story to share about a doctor reacting in that way?

Greg: Sure. One primary care doctor came out of the exam room in the early days of using PatientWisdom and said to a colleague, “I just learned something new about my patient. I've been taking care of her for 13 years. And I didn't know she doesn't like to be called by her first name.” Details like this might seem small, but they are significant because if you want to have a healing relationship with a patient, the minimum daily requirement is having that patient feel like you know him or her. Calling people by a name they don’t prefer is not getting you there. That’s an example of changing what it feels like to get care. PatientWisdom is also changing care itself because many patients are sharing information that they have never said out loud.

Jacqueline: I see. The thing is, many doctors see a particular patient for, say, 15 years but maybe have spent only some hours total interacting with them. Do realizations like this help close the gap between isolated care touchpoints?

Greg: Yes. Different specialties have different average encounter lengths, but what you often hear is “the 15-minute visit” right? While every second of those 15 minutes is precious, even if patients with a chronic illness see their clinician once a month, more than 99 percent of their lives happen outside of the care setting. That’s why we ask patients to share what matters to them. One example is health goals. It’s important for clinicians to know what people are trying to do or having a hard time doing. Do they want to run a marathon or go on a hike with their children next year? How is their health affecting their lives?

“I just learned something new about my patient. I've been taking care of her for 13 years. And I didn't know she doesn't like to be called by her first name.”

Jacqueline: What key insights have you found from asking patients questions like these? What patient responses have specifically caused clinicians to approach their care delivery methods differently?

Greg: First off – and this is an important point – we don’t really ask questions. We designed PatientWisdom to help people share perspectives, not answer questions.

And we're finding that patients are safely sharing things they haven't said to their clinicians before. Maybe they were embarrassed. Maybe they were never asked. Or maybe there just wasn't time.

It makes a big difference. In a randomized controlled trial published by the Journal of General Internal Medicine that we recently completed with one of our health system partners, we found that PatientWisdom generated double-digit increases in the percentage of patients who said that their doctor treated them with respect, showed care and concern, showed interest in their ideas, and spent the right amount of time with them. And it looks like they aren’t spending more time – it’s just better time.

Jacqueline: Let’s get more specific about some key patient findings you’re realizing when you analyze the patient perspectives. Is there anything that’s surprised you that you think healthcare leaders, clinician leaders, and clinicians should all be aware of?

Greg: Yes, one finding comes top of mind. The biggest pressure or worry for most patients revolves around family, ranging from concern about a family member’s physical or mental health to the stresses of being the main caregiver for a family member to how one’s own health impacts the family. Health organizations don’t need to solve this problem, but it helps to be aware, to show empathy, and to offer resources. Seeing family emerge as the major pressure for so many people was pretty surprising.

Here’s a finding that is not a surprise: When given the opportunity, people bring up tangible challenges that interfere with treatment plans. For example, let’s say a patient has diabetes. She has a treatment plan and it’s not working; her A1C is not going down. Both the patient and her doctor are frustrated. The doctor reviews her PatientWisdom inSIGHT summary and sees: “My husband cooks, and he puts sugar in everything.” Now, that's a different kind of conversation. It changes care.

Jacqueline: Let’s dive into some of the data, especially your communication science findings, that analyze tangible, yet invisible holes in patient-physician communication. What does an effective clinical encounter look like?

Greg: An effective clinical encounter requires the execution of essential communication tasks, which have been well defined over the past few decades. The pace of healthcare – and the pace of life in general – makes it increasingly difficult to accomplish these tasks on a regular basis. So we built a tool to make that process more reliable by getting information from patients up-front and providing it to the care team ahead of clinical encounters. As a “communication guy”, I don’t want a digital tool to replace the clinician-patient relationship. I’m just convinced that we can’t expect busy people – and patients are busy, too – to reliably accomplish key communication tasks if there’s not a digital tool to support them.

Jacqueline: You are clearly focusing on fostering human understanding and improving care at the n = 1 level. What are you seeing at the population level?

At the population level, the responses are de-identified. We are running content analysis on the rich open-ended information that patients are sharing. By focusing attention on the themes and subthemes that emerge across patients, visits, or sites, we can help organizations learn and improve. Diving into how people say their health affects their lives is one good example. When you look at patients who have diabetes, for example, people with Type 1 Diabetes have a different pattern of response than do people with Type 2 Diabetes. The bottom line is this: You can't think of “diabetes” as one thing. And you can't think – even though this is at the population level – that all patients with a given diagnosis experience their illness or treatment plan in the same way. Everybody's different. But these subthemes point to topics that might be worth broaching with patients who have these illnesses.

Jacqueline: Switching gears a bit, how did COVID-19 impact your approach?

Greg: When COVID-19 hit, we focused on supporting our partners as care was being redefined. We created and launched CommunityWisdom on Coping with COVID-19 Challenges, which was geared for community members. We did this because what I kept seeing out there early on were surveys about whether people think they have COVID-19 or if they know what it is, and that kind of thing. It was certainly valuable, but I wasn't seeing anything about, “How is this situation affecting you?” So, we wanted to focus on the kinds of stress people were feeling and better understand how they were coping to help guide support efforts.

Then when things started reopening toward the end of last May, we added items on what would make people feel comfortable coming in for healthcare and what kind of healthcare channels they preferred. Respondents pointed to masks, cleanliness, space between people, and plenty of hand sanitizer as the main things that would help them feel safe if they had to go in for care, but were much more comfortable with virtual visits than coming in-person. The world has seen an exponential increase in the use of telehealth and virtual visits since COVID-19 hit. We’ve made more progress in the last several months than in the last 30 years at some level, but the key is to make sure we focus on the people as much as on the technology. It still comes down to effective communication and human understanding.

“When somebody feels like they're drowning, don't hand them a rock. Hand them a lifeline.”

Jacqueline: That’s an interesting realization, especially as mental health takes precedence right now in both healthcare and the mainstream media. One last question: What’s your greater advice for healthcare leaders on how to improve the patient experience and care delivery outcomes?

Greg: The thing to keep in mind is there's a ton of talk about the “digital front door” and mapping the patient journey. All really important. The problem is, when there’s too much focus on making the transaction happen more efficiently, you risk losing the relational aspect. The relational aspect of healthcare is at the core of patient experience, clinician experience, and, to a large degree, care outcomes. We need to shift the frame from transactions to relationships.

Adding in another layer of complexity, clinicians have a compressed schedule, they're running harder than ever, and they feel like they're drowning. That's real life and the pandemic has intensified the pressure. When somebody feels like they're drowning, don't hand them a rock. Hand them a lifeline. Say, “Here's how we can help you.” Healthcare is trying to focus on safety, consumerism, value, and personalization while combatting a pandemic that is devastating and depersonalizing on too many levels. The need to humanize care, for the sake of patients and clinicians, has never been more apparent.