Editor's note: This article is an extension of our Women in Healthcare Leadership research, launched earlier this year. Read more here about how although women dominate healthcare's workforce, few make the C-suite. And learn more about the gender breakdown of healthcare's leadership ranks here.

How do women in healthcare perceive themselves in relation to their jobs and their greater lives? As caregivers, not employees. The over 70 women leaders we spoke with as part of our Women in Healthcare Leadership initiative consistently mentioned they consider their identity as much more than just what they “do” for a living. This was a sentiment shared from those still moving up the ladder to those at its peak.

We noticed through our research that some women mentioned their greater identities in the context of, say, discussing risks they’d taken in their careers, their preferences when working in groups, workplace differences they’d observed over the years between men and women, or the significance their career has compared to other aspects of their lives. Below we highlight our findings, our conclusions, and memorable moments from what some female leaders in healthcare had to say.

Women Prioritize Their Caregiver Identities Over Their Workplace Identities

One key takeaway we learned from our interviews (one we didn’t find surprising): women in healthcare (perhaps like women across other industries, that is) continue to hold more household responsibilities compared to men in healthcare. They therefore tend to value their role as caregiver over the identity they have as leader of an organization.

"Most women have many more roles they have to play in life than men do. Even among the most high-ranking women in the C-suite I know, women still think of themselves as ‘mother’ or ‘caregiver for parents’ right up there.”

"Of the women I’ve talked to, you find very few senior women where their job defines them. If I needed to, I could leave this job tomorrow, and I’d have 80 things to do and roles to fill.”

"When I am here, I give everything I have. I will fight like hell to make sure we’re doing the right thing. At the end of the day, I won’t be buried as CEO. I will be wife, mother, and grandmother.”

Why Does Women’s Broader Sense of Identity Matter?

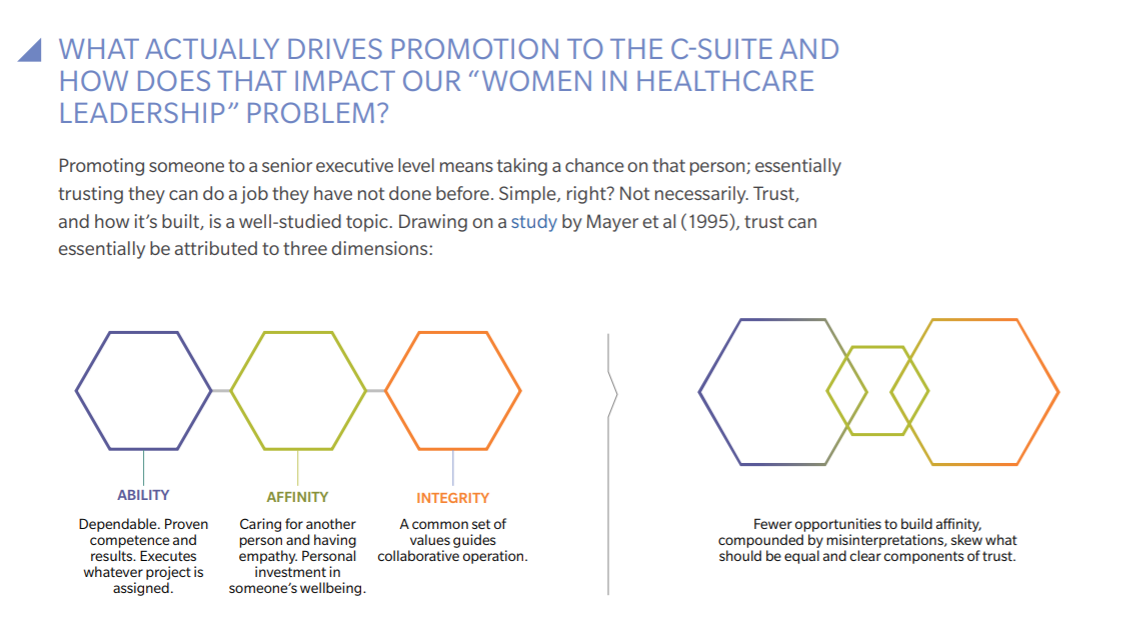

We concluded from our research that a sense of identity beyond work is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s something that’s perhaps culturally more permissible for women than for men – thus, enabling some women to take on more risks in their careers. But in other cases, this extended sense of identity can create more difficult tradeoffs for those women who identify with both their career and caregiver identity. This mindset can also influence how women approach their roles at work and, at times, even drive misperceptions between men and women about each other’s ability.

(Source: An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust, Roger C. Mayer, James H. Davis and F. David Schoorman | Oliver Wyman's Women in Healthcare Leadership Report, 2019)

We perhaps see this latter idea most acutely in how women tend to team and lead at work. Studies have shown men and women actually view collaboration or teaming differently. Case in point, according to Harvard Business Review, women are more likely to agree with the statement,

“Being a good team player means helping all of my colleagues with what they need to get done.”

While men are more likely to agree with the statement,

“Being a good team player is knowing your position and playing it well.”

Women typically view teaming as helping others – eerily similar to what a caregiver role is outside of work. This “team” focus influences women’s leadership styles, as well. Women tend to have a more democratic, empowering leadership style compared to men’s generally more autocratic leadership styles. Women spend more time helping colleagues than focusing on their own priorities or perceptions. Meanwhile, men are more often seen as “staying in their lane” when executing work, less likely to delegate discussions to their team.

"I always believe it's not about me, but about the team.”

"I’m not motivated by ‘How do I continue to advance?’ I’m more motivated by, ‘How do individuals on my team get to the next level? Who’s going to be the next key player on the team?’”

However, these differences can also be easily misinterpreted by one another. Men can perceive women as not owning or driving an initiative forward. It can also make it harder for sponsors to cite specific roles. On the other side, women can view men as territorial and taking credit for the ideas of others.

"Women let other people talk. They think they’re doing the right thing by letting their team present information rather than making it their responsibility. …They don’t have someone telling them, ‘They don’t see you as a leader when you have your team present.’ There’s a balance between promoting your team and promoting yourself.”

"Among the women who want it, there are still notions of whether women have the right chops to be leaders.”

"Men are more defensive when challenged. They walk into a room and do everything, but circle each other. Men are rewarded for showing they’re ‘king of the hill.’”

These differences in leadership styles can spark big misperceptions about ability. As discussed in our Women in Healthcare Leadership research, the ability to demonstrate “leadership” becomes increasingly important (and increasingly abstract) the closer someone gets to the top of an organization. It’s most likely going to be a man making the call of whether someone has “the chops” to be a senior leader.

The perception of someone’s leadership ability is clearly just one piece of the puzzle, but an important one. Leaders must be more explicit about leadership expectations – like defining what’s a core competency versus a stylistic difference – and more open to different styles that are equally as effective but may differ from their own. In an industry beginning to face disruption, the labor of the underlying workforce is becoming increasingly diverse in its skillsets and approaches. To keep up, organizations need leadership teams that do not follow the same form, but rather weave diversity and diverse thinking into their leadership decisions.

For a more in-depth discussion of recommendations for the path forward to gender parity progress, read our full Women in Healthcare Leadership report.