Editor's Note: The following article was originally published in "Brink."

The economic pressure to work well beyond the traditional retirement age is aggravated by two complementary societal trends: increasing income inequality and a substantial weakening of pension plans that deliver adequate, predictable post-retirement income. Both of these trends are leaving many older workers without the financial resources to retire from work completely.

Tapping into opportunities to earn income in the “gig economy” is often proposed as a solution to this challenge. The idea is that gig work can provide a vehicle for older workers to remain productively engaged, but in ways other than traditional employment arrangements that involve full-time employment status. Gig work is about choice and flexibility. Gig workers have freedom to choose —or at least bid on — the type of activities they most prefer to do, with whom, where and when. For older workers, the flexibility of gig work may be very appealing.

How Large a Part of the Economy is Gig Work?

If we restrict the definition to only those who earn income through online platforms such as Airbnb, TaskRabbit and numerous others, an estimated 4 percent of the U.S. workforce engages in gig work.

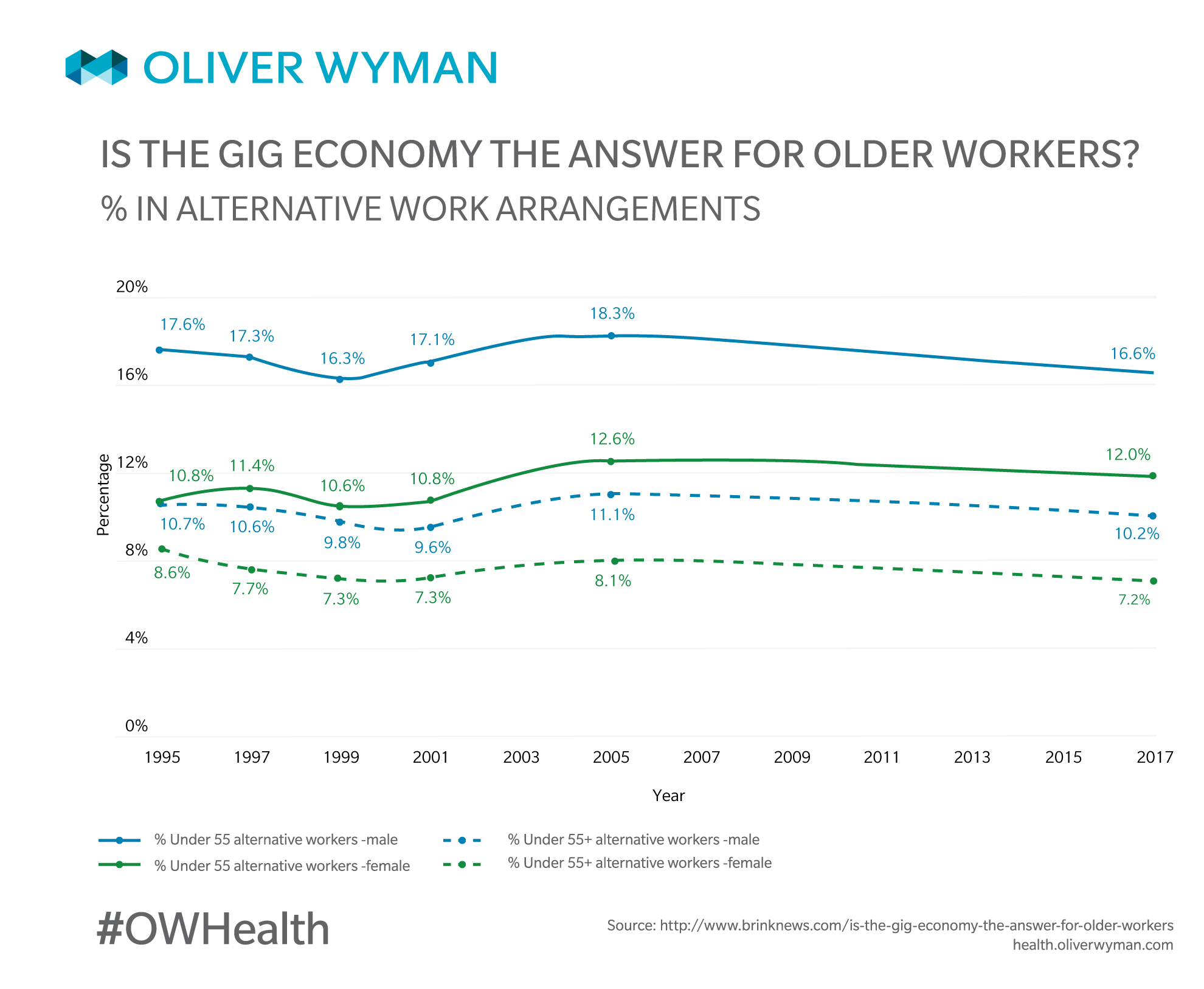

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is inclined to take a broader view. It tracks “alternative employment arrangements,” which include not only platform-based assignments but also independent contracting and temp-agency staffing. BLS estimates that about 10 percent of the U.S. workforce engages in such work as the primary source of income.

Interestingly, older workers, especially men, engage in alternative work arrangements at higher rates than do those under 55.

Continued Work is the Reality

Globally, life expectancy has more than doubled since 1900, and it is forecasted to increase by an additional 4 years between now and 2040. Notable variations by country exist — for example, life expectancy is expected to grow more rapidly in other developed economies than in the U.S. — but the trend toward longer lives is nearly universal. As people live longer, they work longer, and for many who attain an age at which full retirement was once assumed, continued work is now the necessary reality.

Income inequality is also keeping older workers in the workforce. During their prime earning years, today’s typical 60- and 70-year-old experienced an inflation-adjusted 11.2 percent growth in compensation since 1978, compared to more than 900 percent growth for those in the highest income brackets, thus hindering the opportunity to save adequately for later-year expenses.

Especially important to today’s older workers is the disappearance of employer-provided defined benefit pension plans. The loss of defined benefit income exacerbates income inequalities, diminishes the incentive to retire, and often reduces the availability of the resources required to sustain retirement.

Can Gig Work Fill the Pensions Gap?

As appealing as the flexibility of gig work might be, income from gig work is rather modest. According to the JPMorgan Chase Institute, earnings through platform-based gig work typically are less than $1,000 per month. Further, based on the reviews of loan applications, earnest.com estimates that average monthly earnings from gig work are $299 per month and under $110 per month for half of all gig workers.

While for some the income from gig work will be just what’s needed to supplement income from retirement savings, for many older workers, gig earnings will fall far short of what’s needed to overcome what could be precarious financial circumstances, especially when compounded by the absence of pension income and the lack of employer-accessed health and insurance benefits with gig work.

Working With Robots

Another important development is technology’s disruptive impact: robots, automation and artificial intelligence. Robots can take over heavy lifting or precise movements required in a manufacturing process, thus enabling older manufacturing employees to stay in their jobs longer, but only if those employees adapt to the new requirements that automation brings.

Advances in technology require workers of all ages to “keep up with the times” and there’s a suspicion that older workers cannot keep pace with technological change. Older workers may be disadvantaged if they are not accustomed to a lifetime of learning, although many older workers are so accustomed.

Older workers may also be disadvantaged by unfamiliarity with some aspects of technology, such as gamification. Younger cohorts of gamers may be more favorably positioned to score well on a gamified employment test or training module.

While there are legitimate reasons to believe that older workers may be put at a disadvantage by some aspects of technology, it would be a great mistake to assume that older workers are uniformly unable to learn and adapt.

The Line Between Work and Retirement is Blurring

Many of the skills and competencies required to effectively operate manufacturing plants relying on advanced technologies are those more often associated with older, not younger, workers. Unwarranted age-based assumptions — ageism — is a reality that can greatly harm older workers.

The hard boundary between “work” and “retire” is gone. Milestones of “retirement age” have become obscure, and the meaning of retirement itself is evolving as people increasingly engage in alternative forms of work later in life.

Yet a lot of employers — through existing pension rules, benefits practices and staffing policies — have frozen themselves into an outdated world view: Go to school, work, retire. As a consequence, these employers are poorly positioned to take advantage of the business value of the experience and skills that older workers possess.

Mixing Benefits and Work

More creative solutions are needed for this growing segment of the workforce. For example, employers could implement gig-like work arrangements inside their organization for current older employees, arrangements that provide the aspects of gig work that older workers value while still maintaining employee status.

Or, rather than “forcing” an employee into retirement to begin a stream of pension income, perhaps employers with pension plans could better align their rules to today’s realities by enabling partial pension payments to eligible (older) employees — for example, enabling employees to collect partial pension payouts while engaged in alternative work arrangements.

Older employees can be expected to be keenly sensitive to certain benefits eligibilities; perhaps more appealing menus of compensation and benefits can be designed to appeal to older employees and support their continued contributions to the business. Older workers are the new strategic challenge for employers. Expanding older worker engagement in the gig economy may be part of the required response for employers, but it is unlikely to succeed alone. An unfreezing of practice and policy is needed to solve the longevity challenge.