By Jeremy Sporn and Stephanie Tuttle

This article first appeared on Harvard Business Review on June 6, 2018.

An Arabic version of the article was written for Harvard Business Review Arabia on August 6, 2018.

Retail has been constantly reinventing itself, and participants race to keep up with what feels like a series of epic shifts in consumer preferences. Apparel brands are investing especially heavily in online shopping capabilities and introducing interactive features that complement apps and websites. Retailers and manufacturers are rushing out new products to keep pace with the leaders of fast fashion such as Zara, H&M, and Forever 21, which launch new fashions every week or so.

But do consumers actually crave all of these changes? And which approaches can generate growth in this changing environment? Many manufacturers try to answer these questions using point-of-sale data, which often comes filtered by the retailers that gather the information; media coverage, which tends to focus on the new; and previous sales of their products, which reflect the past.

We studied the actual decisions made by 1,500 apparel and footwear shoppers in the United States. The results showed that retailers need to look beyond the buzz surrounding retail and instead focus on specific aspects of consumer behavior if they hope to improve their businesses and drive growth

To get a clearer, more-complete picture, we studied actual decisions made by 1,500 apparel and footwear shoppers in the United States. We asked them about everything from their initial motivation to shop, to the shopping journey itself, to how they felt after making their purchases.

The results showed that retailers need to look beyond the buzz surrounding retail and instead focus on specific aspects of consumer behavior if they hope to improve their businesses and drive growth. According to our research, many assumptions about the ongoing revolution in retail are, in fact, myths.

Below are five of our most surprising findings.

Myth: Shopping has become truly omnichannel.

Fact: Most journeys are still overwhelmingly single-channel, though this is changing.

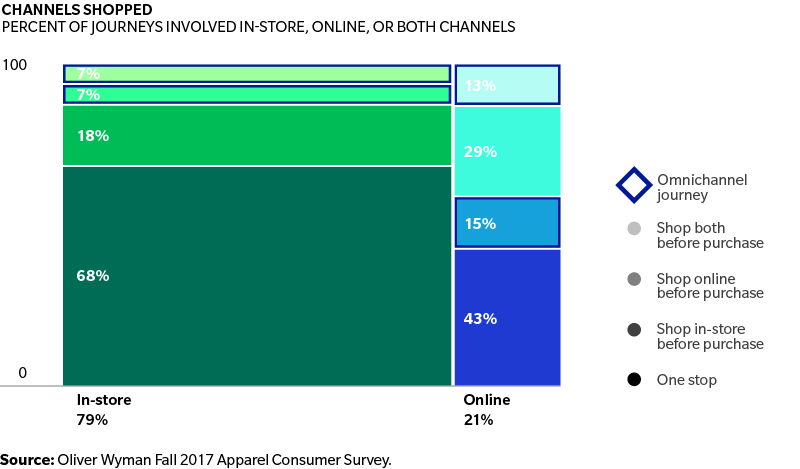

The buzzword of recent years has been omnichannel, meaning that consumers are thought to combine store visits and online interactions during their shopping journeys. However, while omnichannel is growing in importance, our study suggests that 83% of shopping journeys still happen within a single channel — overwhelmingly in traditional stores, which account for almost 80% of apparel purchases today.

Apparel companies and independent retailers need to continue to focus on making their physical stores attractive to visit so that they ultimately become more-effective contributors to brands’ financial results. One area where they trail is knowledge of the customer. Online sites have a wealth of data on shoppers — from their tastes, as indicated by previous purchases, to demographic information and preferences. In a store, however, a sales associate tries to guess a shopper’s tastes in real time. As a solution, technology could be used to customize the in-store experience by encouraging customers to swipe their smartphones as they enter, so that their profile could then be used to tailor the experience and offers. Stores should also make shopping memorable — through drinks and other hospitality services, for example — and encourage customers to complete their transactions online.

Myth: The sales channel doesn’t matter.

Fact: When consumers purchase online, they tend to buy more.

Shopping journeys concluding in online purchases have baskets that are 25% larger, on average. When someone first visits a physical store and then purchases online, the effect is even more pronounced: Baskets are 64% larger.

One reason why is that free shipping often comes with a minimum basket size, so customers often select extra items to reach this threshold. Another is the greater product range available online without the need to carry inventory in a prime-location store. Moreover, it is relatively easy to create impulse purchases online from information gathered about the shopper and to incentivize larger basket sizes.

To benefit, retailers with physical stores should make a concerted effort to drive in-store customers to their website to make their purchases. This is what Bonobos does: It encourages shoppers to experience a product in its “no-inventory” stores and then complete the order online.

Myth: Online shopping is about instant gratification.

Fact: Online journeys tend to be longer than in-store.

Shopping with clicks sounds like a speedy process. But consumers actually take more time online than when shopping in physical stores, and they make more stops. In fact, 57% of shopping journeys that conclude with an online purchase begin with a consumer either first looking at another website (29%), visiting a brick-and-mortar store (15%), or both (13%) before ultimately transacting online through any particular retailer. The other 43% of journeys that conclude with an online purchase are one-stop journeys that begin and end with the same online retailer.

This means that online shoppers are doing a lot of comparison, so online retailers should work harder to close sales quickly while they have the attention of the consumer. They can do this by actively sending cart recovery messages or creating loyalty programs for a particular site. Removing hassles could help: More than 10% of consumers indicated that they had abandoned a cart on a website and then bought the items elsewhere simply because they didn’t like the first site’s shipping or return policy.

Myth: The retailer doesn’t matter.

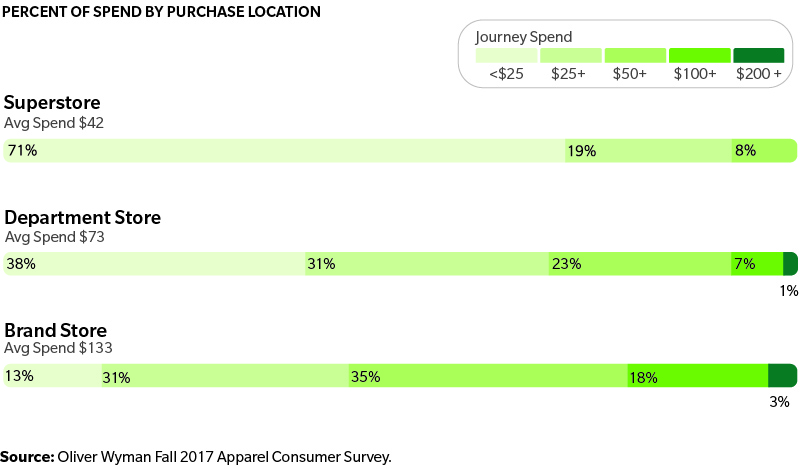

Fact: Spend is dramatically higher at brand stores and websites than in multibrand stores.

Direct-to-consumer brand stores and websites generate revenues 86% higher than purchases of those same brands elsewhere — and, of course, better margins. A specific store or site may make a brand feel more valuable and differentiated to customers, inducing them to spend more than they would otherwise. Direct-to-consumer channels also help to develop (or maintain) a brand’s image.

This means brands could benefit from driving consumers toward their own sales channels, though of course in a way that does not jeopardize their relationships with retail channel partners such as department stores. One important strategy is stocking unique products available only from a brand’s website or store. Nike has had some success with this strategy, and has gone one step further by allowing people to customize their products on its website. Other apparel brands might seek to attract customers through differentiated and personalized products.

Myth: Consumers always want something new.

Fact: Very often, they are happy to rebuy the same or a similar item.

Fast fashion has become a buzzword for apparel makers, but many consumers are simply looking to replace an item they already have. This is especially true in intimates and basics, but also in fashion, where the aim of 83% of shopping journeys is repeat purchases, and athletic products (87%).

Brands should, to some extent, change their mindsets: Success could mean finding consumers that like a product and reselling it to them, and not always trying to reinvent the wheel. The customer, not the product, should come first. Repurchasing of products previously bought could be made easier through promotions on similar items, tailored advertising for new versions, reminders when a product likely needs to be replaced, and even subscription services. To get to know customers better, brands might encourage them to go online during trips to physical stores and to comment on products through apps. Manufacturers can then follow up and encourage repeat purchases.

Eventually, brands and retailers should integrate their e-commerce units into the rest of their commercial organizations, replacing channels that compete for sales from the same customer with a structure that puts the customer first

Acting on these findings implies going beyond technology fixes and making changes to a company’s organizational structure. At a minimum, physical stores and e-commerce operations would benefit from better links. For example, internal financial systems need to accurately reflect a customer’s buying an item online and later returning it to a physical store. Eventually, brands and retailers should integrate their e-commerce units into the rest of their commercial organizations, replacing channels that compete for sales from the same customer with a structure that puts the customer first. In the future, customers will decide where and how they shop, and the apparel business must make this as smooth — and profitable — as possible.

This article is posted with permission of Harvard Business Publishing. Any further copying, distribution, or use is prohibited without written consent from HBP - permissions@harvardbusiness.org.

Additional articles: